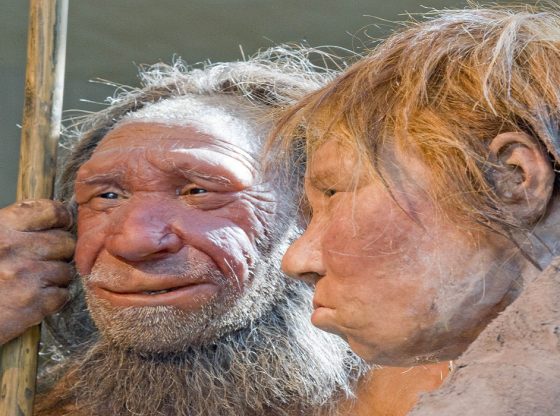

The complete genome of a neanderthal has been mapped for a second time. The new findings sheds light on archaic human admixture with modern humans and how it impact us today.

The Neantharthal genome has been analyzed six times, but this is the second time the complete genome has been mapped. The first time the entire genome was mapped, the remains of a Neanderthal found in Siberia was used. This time, scientists used DNA from bone fragments from a neanderthal individual found in a cave in Croatia.

Neanderthal Legacy

The analysis enables scientists to reveal even more about the genes that we humans have inherited from Neanderthals – since it was first revealed that intercourse took place between Homo Neanderthals and Homo Sapiens and that genes were passed down to modern humans.

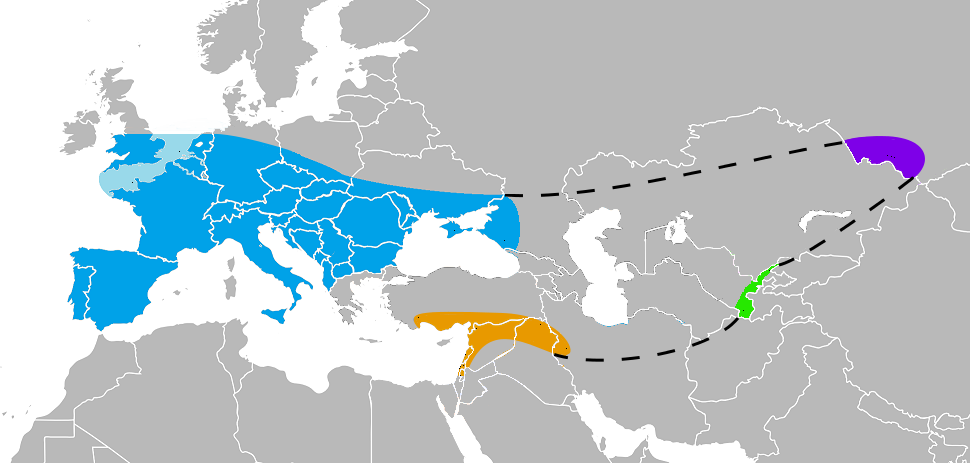

Modern humans carry specific genetic variables that can be derived directly from the Neanderthals. These genetic variants are found in all the Earth’s people besides those of African descent, the researchers, therefore, suspect that the interspecies mixing took place somewhere near the Middle East some 100,000 years ago, although the new analysis provides new evidence of even older interbreeding.

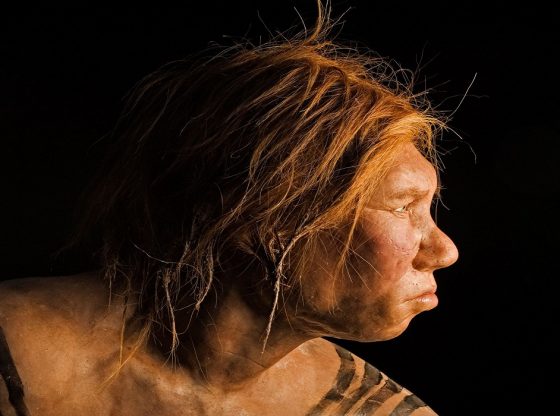

Neanderthals had a larger impact on the DNA of modern humans than previously thought. Among the genes that we received from our cousins are genes involved in everything from our skins ability to tan, our hair color, metabolism, our immune systems, high cholesterol levels, vitamin D production and schizophrenia. As first shown in a a study published last year when the complete Neanderthal genome was first mapped.

The Croatian neanderthal whose DNA has now been analyzed lived closer in proximity to the groups that mixed with modern humans and could, therefore, provide even more valuable insight. The neanderthal woman lived in the Vindija cave in Croatia about 52,000 years ago.

1.8-2.6 Percent

The new analysis, published in the journal Science, shows, among other things, that the contribution of cousins to our own genome is somewhat larger than previously thought. Probably, the researchers write, 1.8-2.6 percent of our genome today can be derived from the Neanderthals. This is more than the previous estimates of about 1.5 to 2.1 percent. East Asians have about 2.3 to 2.6 percent Neanderthal DNA, while those with ancestry in western Europe and Asia have retained about 1.8 to 2.4 percent DNA.

Among the genes that we inherited are significant genes involved in obesity, rheumatoid arthritis, high cholesterol levels, and how we react to antipsychotic drugs.

The previous complete Neanderthal analysis suggested that Neanderthals starting breeding with archaic modern humans around 100,000 years ago, but the new analysis pushes that back even further to between 130,000 to 145,000 years ago.

Another study based on the same analysis and published in the American Journal of Human Genetics shows that we have inherited properties for how our skin reacts to sunlight, our ability to tan, also, genes that regulate skin and hair color. In fact, the researchers note that half of all the Neanderthal genes in our genome play a role in determining skin and hair color.

They also found that Neanderthal genes play in human sleep patterns, as determined by the body’s circadian rhythms. This is medically important information since circadian rhythms affect variation in blood levels of glucose, insulin, and leptin, which controls our appetite. It also underpins short sleep episodes, sleeps deprivation and poor-quality sleep – associated with diabetes, metabolic syndrome, increased appetite, and obesity.

They found a link between latitude and the prevalence of a Neanderthal form of a gene (ASB1) which plays a role in determining whether you are an “evening person”. Non-African populations living further away from the equator today, show a higher prevalence of ASB1 than people living close to it.

They found genes linked to the height of adults as well as the stature reached by children at 10 years of age, the pulse rate, and the distribution of fat in the legs. Lastly, they found Neanderthal genes that determine our mood, as influenced by our exposure to sunlight, even those that determine if we like to eat pork or not.

Human Adaptation

Hybridization was probably a quite creative evolutionary force when humans were colonizing the planet and were forced to adapt to different geographical biotopes and climatic endowments.

Beneficial genetic traits can arise through chance mutations, but we might be waiting for a long time for such events to take place. Interbreeding can speed up these changes.

Homo Neanderthals and Denisovans have been living in environments foreign to us humans, adapting to unique geographical features over vast periods of time. Homo Neanderthal is believed to have been living in Europe for 600,000 years before Homo Sapiens arrived – evolving to the unique conditions that characterize the continent.

A previous study showed that a high-altitude gene helps Sherpas and other Tibetans breathe easy at high altitudes was inherited from the ancient species of human known as Denisovans.

When modern humans left Africa, integrating with other species, therefore, allowed us to adapt to new environments much more quickly.

When we humans first arrived in Europe, we may have struggled to deal with unfamiliar local diseases, the climate, and the low amount of sunlight that characterize Northern Europe, but the offspring of those that interbred with Neanderthals fared better.

Future genetic analysis of much older human specimens might reveal even more about just how much hybridization has shaped who we are today.

Reference:

Kay Prüfer et al. A high-coverage Neanderthal genome from Vindija Cave in Croatia. Science October 5, 2017. DOI: 10.1126 / science.aao1887

Michael Dannemann, Janet Kelso The Contribution of Neanderthals to Phenotypic Variation in Modern Humans DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.09.010 |

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55136/b1b0b614-5b72-486c-901d-ff244549d67a-350x260.webp)

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55124/79bc18fa-f616-4951-856f-cc724ad5d497-350x260.webp)

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55099/2638a982-b4de-4913-8a1c-1479df352bf3-350x260.webp)