The ability to walk on solid land occurred in the sea, long before there were land animals. The nerve cells that control the ability to walk has been found in vertebrates for over 400 million years, according to a new study.

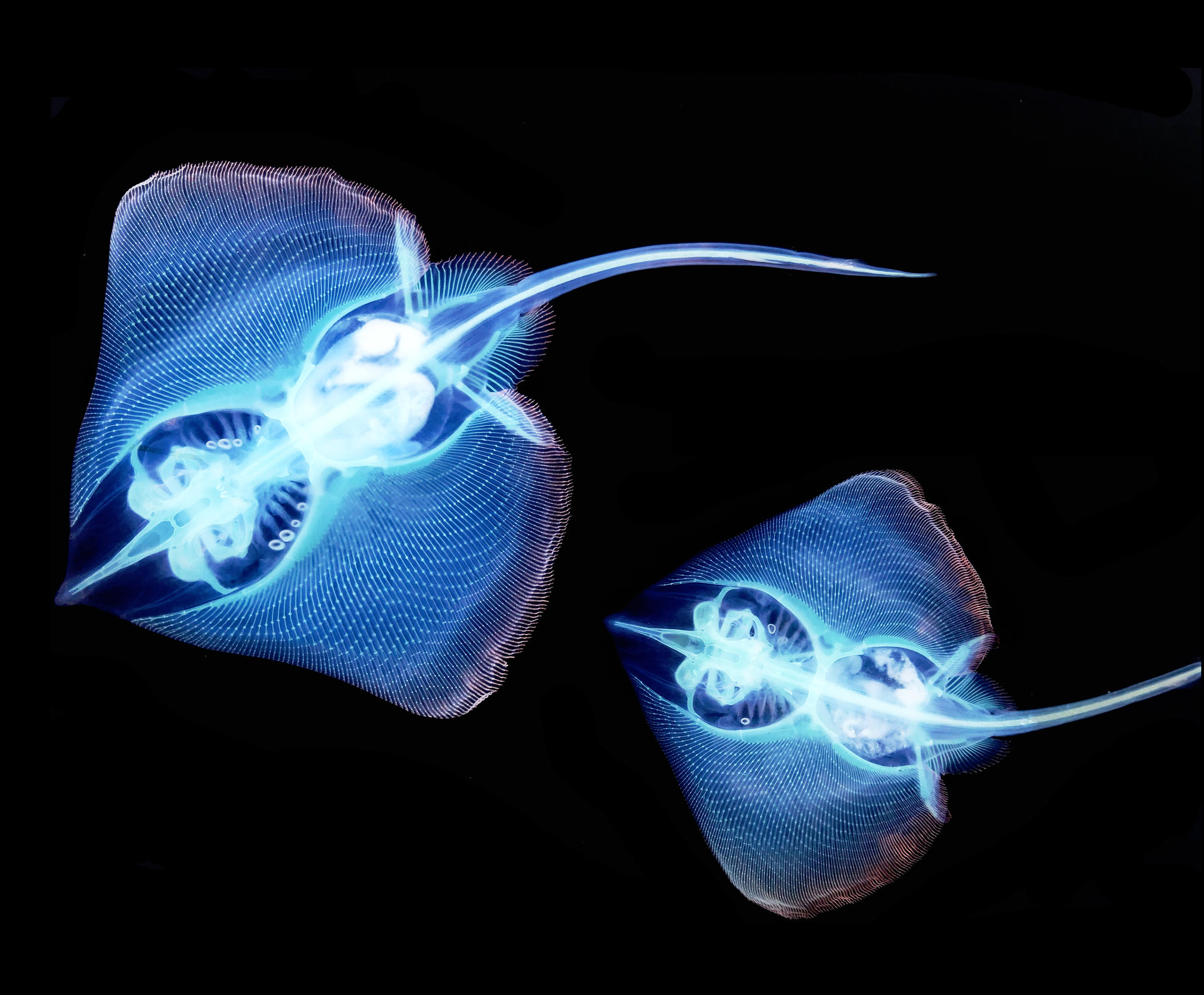

In the study, published in the magazine Cell, researchers in the United States, Australia, and Singapore have examined the genes and nerve cells of the little skate (Leucoraja erinacea).

This skate fish is a typical representative of the family cartilaginous fishes, which also includes the sharks (superorder Selachii) and the rays, skates, and sawfish (superorder Batoidea).

Like many other species of fish living in proximity to the seafloor, the species has the ability to “walk” on the seabed with its abdominal fins.

When we humans walk, we move both feet alternately, one foot and then the other. Similarly, the little skate alternates its fins on the right and left sides of the body. The similarity is striking.

The researchers found that what makes this possible with this fish species is a set of special nerve cells.

Surprisingly, it is the same nerve cells that give humans and other mammals the ability to walk on two or four legs – even though we extremely distant relatives. The last common ancestor of cartilaginous fishes and mammals lived 420 million years ago.

The conclusion is that these nerve cells, and the genetic machinery that controls them, are also extremely old date and are something that all vertebrates have in common, whether they live in water or on land.

In other words, the ability to walk is a very primitive adaptation. Our ancestors walked on the seabed long before the first land animals appeared on land.

“It has been a general belief that the ability to go is something that developed when the vertebrate had risen ashore. But it’s much older than that”

– Jeremy Dasen, lead author and a neurobiologist at the New York University School of Medicine in the United States.

Reference:

http://www.cell.com/cell/fulltext/S0092-8674(18)30050-3

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55136/b1b0b614-5b72-486c-901d-ff244549d67a-350x260.webp)

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55124/79bc18fa-f616-4951-856f-cc724ad5d497-350x260.webp)

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55099/2638a982-b4de-4913-8a1c-1479df352bf3-350x260.webp)