Neanderthals may not have sported the barrel-chested bodies and hunched posture we see in museums and textbooks, according to a new study.

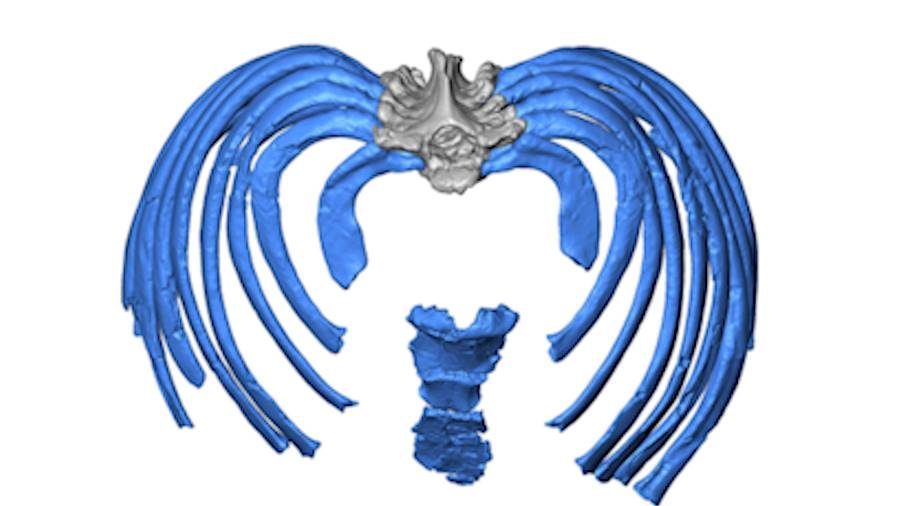

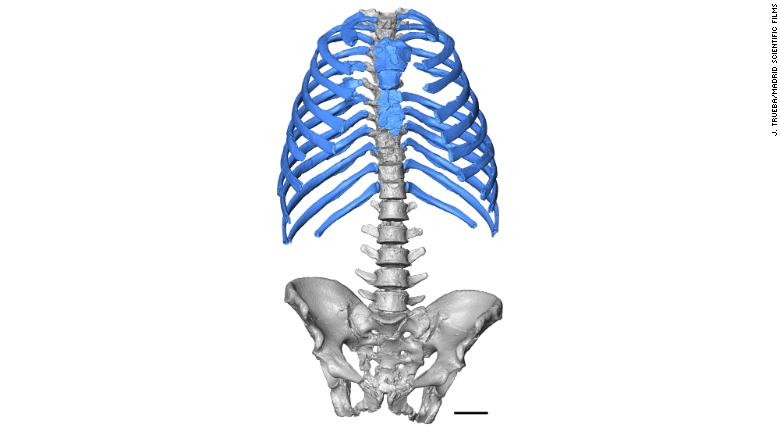

The first 3D virtual reconstruction of a Neanderthal ribcage has revealed that they had straighter spines and a greater lung capacity than modern humans. The findings of the Neanderthals were published last week in the journal Nature Communications.

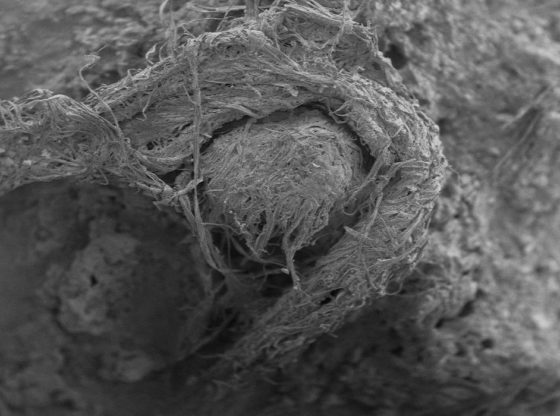

Using CT scans of fossils from an approximately 60,000-year-old male skeleton, researchers were able to create a 3D model of the chest – one that is different from the longstanding image of the barrel-chested, hunched-over ‘caveman’.

“The shape of the thorax is key to understanding how Neanderthals moved in their environment because it informs us about their breathing and balance,”

“Neanderthals are closely related to us with complex cultural adaptations much like those of modern humans, but their physical form is different from us in important ways,”

“Understanding their adaptations allows us to understand our own evolutionary path better.”

– Asier Gomez-Olivencia, an Ikerbasque Fellow at the University of the Basque Country and the study’s lead author.

The CT scans of the fossil of a male skeleton known as Kebara 2, the researchers were able to create a 3D model of the chest. They then used a technique called morphometric analysis to compare the images of Neanderthal bones with medical scans of bones from present-day adult men. The researchers’ conclusions point to what may have been an upright individual with greater lung capacity and a straighter spine than today’s modern human.

Neanderthal ribs connected to the spine more inwardly, which forces the chest cavity out and causes the spine to tilt back. The result is a spinal column that lacks the lumbar curve of modern humans. This skeletal structure not only provided Neanderthals with more stability but allowed for a larger diaphragm and more lung capacity.

The skeleton analyzed by the research team was first uncovered in 1983 in Israel’s Kebara Cave, is considered to be the most complete Neanderthal remains to date, although missing a cranium. In life, the male Neanderthal, known as Kebara 2, stood around 168 centimeters (5 1/2 feet) tall and weighed 75 kilos (166 pounds). He walked the planet about 60,000 years ago and died at the age of 32.

The novel 3D modeling used in the study could open up this field of research.

Reference:

Asier Gómez-Olivencia et al. 3D virtual reconstruction of the Kebara 2 Neandertal thorax https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.7012256

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55136/b1b0b614-5b72-486c-901d-ff244549d67a-350x260.webp)

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55124/79bc18fa-f616-4951-856f-cc724ad5d497-350x260.webp)

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55099/2638a982-b4de-4913-8a1c-1479df352bf3-350x260.webp)