A new large research study shows how the ancient Scandinavians conquered parts of Europe during the Viking Age, from the end of the eighth century to 1050. But the DNA analysis also shows how people from outside flowed into Scandinavia during the same period.

Most of what we know about the Vikings derive from written sources, sometimes recorded several hundred years after the events took place, or through archaeological finds and chemical analyzes of remains.

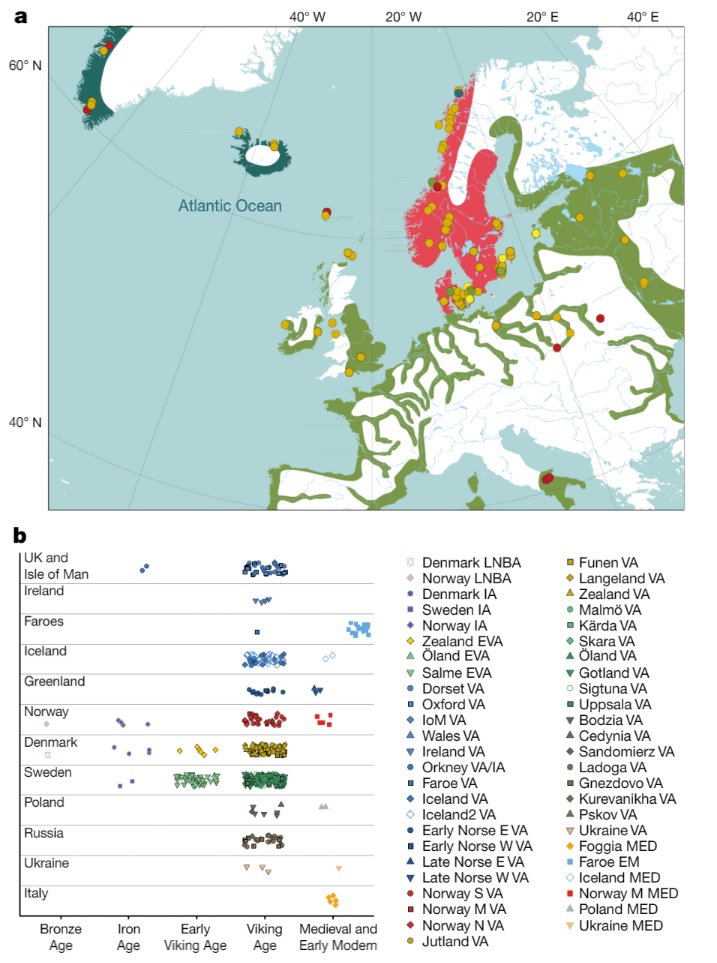

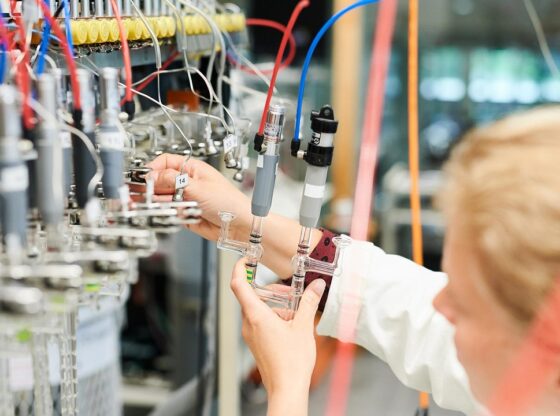

Now a large research team has mapped genes from more than 400 skeletal finds, from the Bronze Age onwards. And DNA technology provides an even more nuanced picture of history than has previously been the case.

“To explore the genomic history of the Viking Age, we shotgun- sequenced DNA extracted from 442 human remains from archaeological sites dating from the Bronze Age (about 240) to the Early Modern period (about 1600). The data from these ancient individuals were analyzed together with published data from 3,855 present-day individuals across two reference panels (Supplementary Note), and data from 1,118 ancient individuals.”

The new analysis published in the scientific journal Nature shows that there were very small genetic differences between the people who lived in the geographical areas in what is now today’s Denmark, Sweden, and Norway. These small differences in DNA meant that researchers were able to trace how these ancient Scandinavians moved around in Northern Europe, 1,000 years after their death.

The results confirm much of what archaeologists have already concluded; Norwegian Vikings mainly traveled west to Ireland and Greenland, Danes colonized the British Isles, and people from present-day Sweden most often went eastwards towards the Baltics, Russia, down to the Black Sea and Byzantine Empire.

However, DNA research shows that there are plenty of exceptions to the rule. You will find Danish Vikings in Österled and people of “Swedish” descent in the west.

Others seem to have perceived themselves as Vikings despite the fact that they had no genetic connection to the Nordic countries at all. Researchers have analyzed bones from typical Viking tombs in the Orkney Islands north of Scotland and found that the people there do not show any relationship with Scandinavia.

At the same time, the DNA study shows that many people have moved to Scandinavia during the same period. In today’s Sweden, there is an influx from Finland and the Baltics, while Denmark received people from the near south, today’s Germany, and the British Isles.

The most mixed population can be found in places along the trade routes of that time. People who lived in Fröjel and Kopparsvik on Viking-era Gotland, for example, seem to have been more closely related to Danes, Britons, and Finns than to people from present-day Sweden.

Conversely, those who lived far from the trading places – including in the interior of Sweden – hardly seemed to have been affected at all by any genetic influx during the Viking Age.

The article in Nature also reveals that the Nordics’ ability to tolerate milk was fully developed only during the Viking Age and not much earlier as was previously thought.

Reference:

Ashot Margaryan et al. Population genomics of the Viking world Nature | Vol 585 | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2688-8

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55136/b1b0b614-5b72-486c-901d-ff244549d67a-350x260.webp)

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55124/79bc18fa-f616-4951-856f-cc724ad5d497-350x260.webp)

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55099/2638a982-b4de-4913-8a1c-1479df352bf3-350x260.webp)