A mass grave believed to derive from the ‘Great Heathen Army’ that invaded Britain in the late 800’s was discovered in the 1970s. But because of an error measurement, the finding fell into oblivion and was forgotten. Now, more than 40 years later, the mass grave makes a large-scale comeback as one of the most important Viking findings ever.

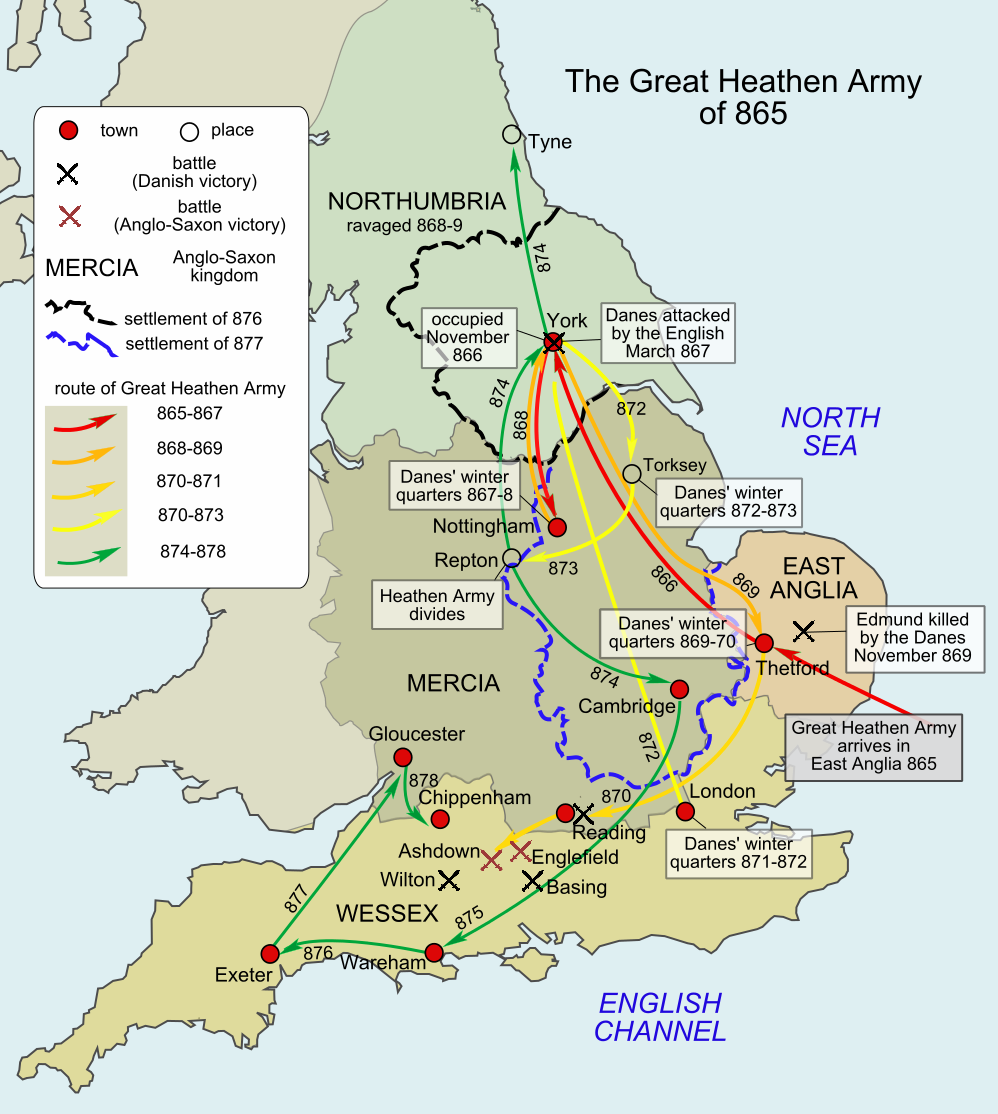

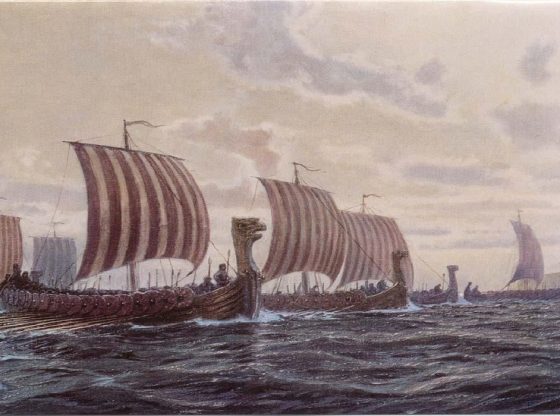

According to legend, it was the three sons of the Danish-Swedish Viking king Ragnar Lodbrok who led the great army that invaded England in 865, which several years later resulted in the so-called Danelaw by which Vikings ruled over a large part of Britain.

In the winter of 873, the army, or “Great Heathen Army”, as it is called in the Anglo-Saxon chronicles, had made winter camp in Repton in central England. In doing so, they made use of a nearby monastery, The Repton Charnel, and its funeral site used by ancient Anglo-Saxon kings.

It was at that site, underneath a shallow mound by St Wystan’s Church vicarage in Repton, Derbyshire, where archaeologist Martin Biddle and Birthe Kjølbye-Biddle in the mid-1970s discovered a mass grave with the remains of at least 264 people.

The archaeologist was convinced that the bone remains were derived from a Viking army. But when the bone fragments were dated in the 1980s using the carbon 14 method, the results came out completely different. Some remains were indeed from the period of Viking presence in Britain, while others were dated to hundreds of years earlier.

The couple Marin and Birthe Biddle never doubted, however, but many others questioned the findings saying that the remains were probably gathered together by the monks at the monastery centuries before the Vikings, so the finding more or less fell into oblivion.

But then, just a few years ago, it was discovered that the carbon 14 method is not perfect when dating an individual that has eaten a lot of seafood during his lifetime. Since the carbon contained in fish and shellfish is derived from atmospheric coal circulating in the oceans for about 400 years before it ends up in the fish. And since the Vikings, famous for seafaring, had a high-seafood diet it would naturally screw up the data.

“When we eat fish or other marine foods, we incorporate carbon into our bones that is much older than in terrestrial foods,”

“This confuses radiocarbon dates from archaeological bone material and we need to correct for it by estimating how much seafood each individual ate.”

– Lead archaeologist Cat Jarman, according to a University of Bristol press release.

This source of error is now easy to take into account, but then – in the 1980s – it was unknown to science. Now, researchers dated the bone fragments again, using a more refined technique.

Their findings have been published in the journal Antiquity and suggests those initial dates were incorrect, and that the timing is right for the remains to hail from the Great Army.

The new dating fits perfectly and shows that all bone fragments originate from the Great Heathen Army and the year 873. The researchers cannot affirm that all of the remains are from Vikings, however, but the evidence most certainly suggests that they are.

Within the mound, there was evidence of 264 bodies, the majority of which were young men, alongside Viking weaponry and artifacts. Some of the skeletons showed signs of violent injury, adding further to the evidence that they came from an invading force.

Reference:

Catrine L. Jarman, Martin Biddle, Tom Higham and Christopher Bronk Ramsey The Viking Great Army in England: new dates from the Repton charnel https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2017.196

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55136/b1b0b614-5b72-486c-901d-ff244549d67a-350x260.webp)

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55124/79bc18fa-f616-4951-856f-cc724ad5d497-350x260.webp)

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55099/2638a982-b4de-4913-8a1c-1479df352bf3-350x260.webp)