Battles change the course of history, they win wars, they topple thrones and redraw borders. Battles have been a part of human history since the beginning of time. They are an intricate part of wars and the events that set the path of events to follow, as instruments molding the future.

By deciding which group, nation or alliance that ends up victorious, they influence the spread of ideology, culture, civilization and religious dogma. Some battles are not directly influential on the path of history on their own, but rather, influential as instruments of propaganda with an impact on public opinion.

This series of articles highlights some of these decisive engagements, but rather than ranking the battles according to their influence on history. Each article will detail the narrative, what happened, what the participants, the leaders and the people of that time thought in those rare cases where their words have been documented parts of history.

Please see the article tag Biggest battles in history series for more articles on the biggest and bloodiest battles in human history.

World War I

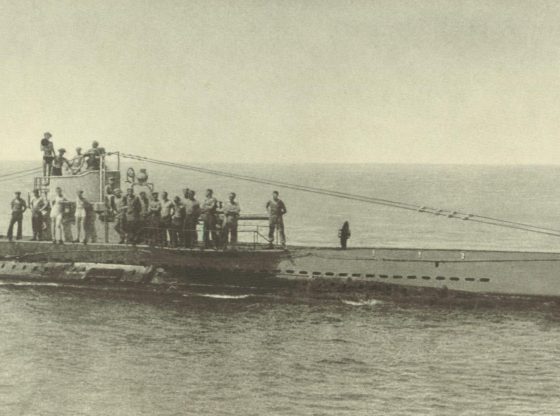

The First World War (1914-1918) was something new in human history as the number of people involved and the devastation of the newly developed weapons and machinery became apparent – this war was thought as the war to end all wars.

Old military tactics meet with new technology that made the same old tactics obsolete by the most gruesome ways imaginable. This war was particularly deadly with human causalities often almost beyond comprehension. Several battles exceed 500,000 casualties. To mention a few, The battle of Somme, The battle of Verdun, The Brusilov Offensive, The Spring Offensive, The Battle of Passchendaele and the First Battle of the Marne.

The Battle of the Somme

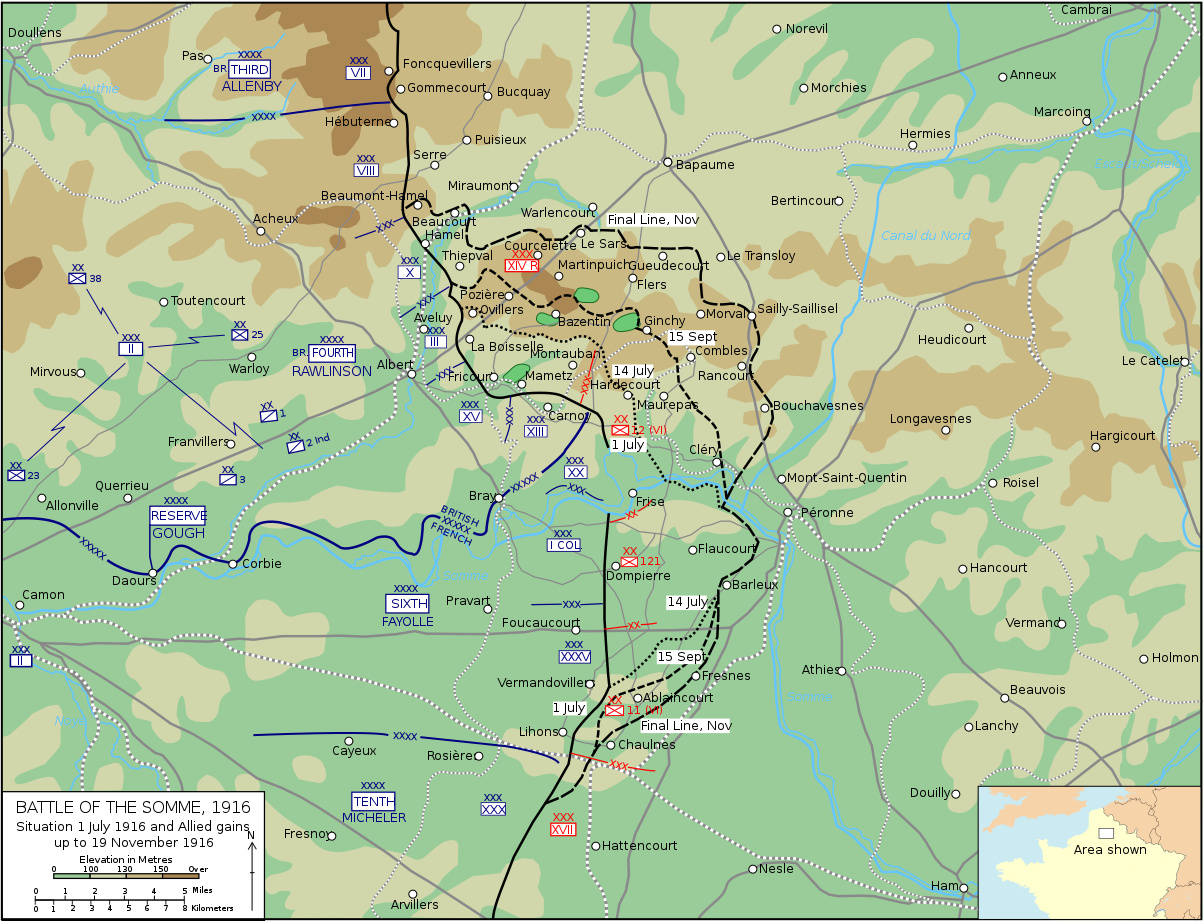

The battle took place in northern France during the First World War and is often considered the world’s largest battle. It began with a French-British offensive against the Germans on July the 1st in 1916 and raged on with few interruptions until November 1916.

The losses were enormous. The British lost about 420,000 soldiers, the French 200,000 and the Germans a little over 500,000 soldiers. During a single day in July, more than 60,000 British soldiers lost their lives.

The reason to why this battle and so many others during World War I was so bloody was because of technological development making defense weapons far superior to offensive weapons.

Soldiers in trenches stretching for miles attacked in mass assaults with bayonets against barbed wire, artillery, machine guns, poisonous gas, flamethrowers, and much more effective means of communication – making coordination and logistics easier for the defending side.

As soon as the enemy tried to force the trenches, they were gunned down with these terrible new weapons. Despite this, the generals sent their soldiers on pure suicide missions in wave after wave. When the battle of the Somme ended, the British had advanced between 10 to 30 kilometers (6 to 18 miles).

We have not advanced 3 miles in the direct line at any point. We have only penetrated to that depth on a front of 8,000 to 10,000 yards. Penetration upon to narrow a front is quite useless for the purpose of breaking the line. In personnel the results of the operation have been disastrous; in terrain, they have been absolutely barren… from every point of view, the British offensive has been a great failure.

– Winston Churchill’s memorandum in July 1916 (then commanding the 6th Battalion of the Royal Scots Fusiliers, with the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel) presented to the War Cabinet by his friend F.E. Smith

The trench was a horrible sight. The dead were stretched out on one side, one on top of each other six feet high. I thought at the time I should never get the peculiar disgusting smell of the vapor of warm human blood heated by the sun out of my nostrils. I would rather have smelt gas a hundred times. I can never describe that faint sickening, horrible smell which several times nearly knocked me up altogether.

– British Captain Leeham, talking about the first day of the Battle of the Somme, in ‘Tommy Goes to War’

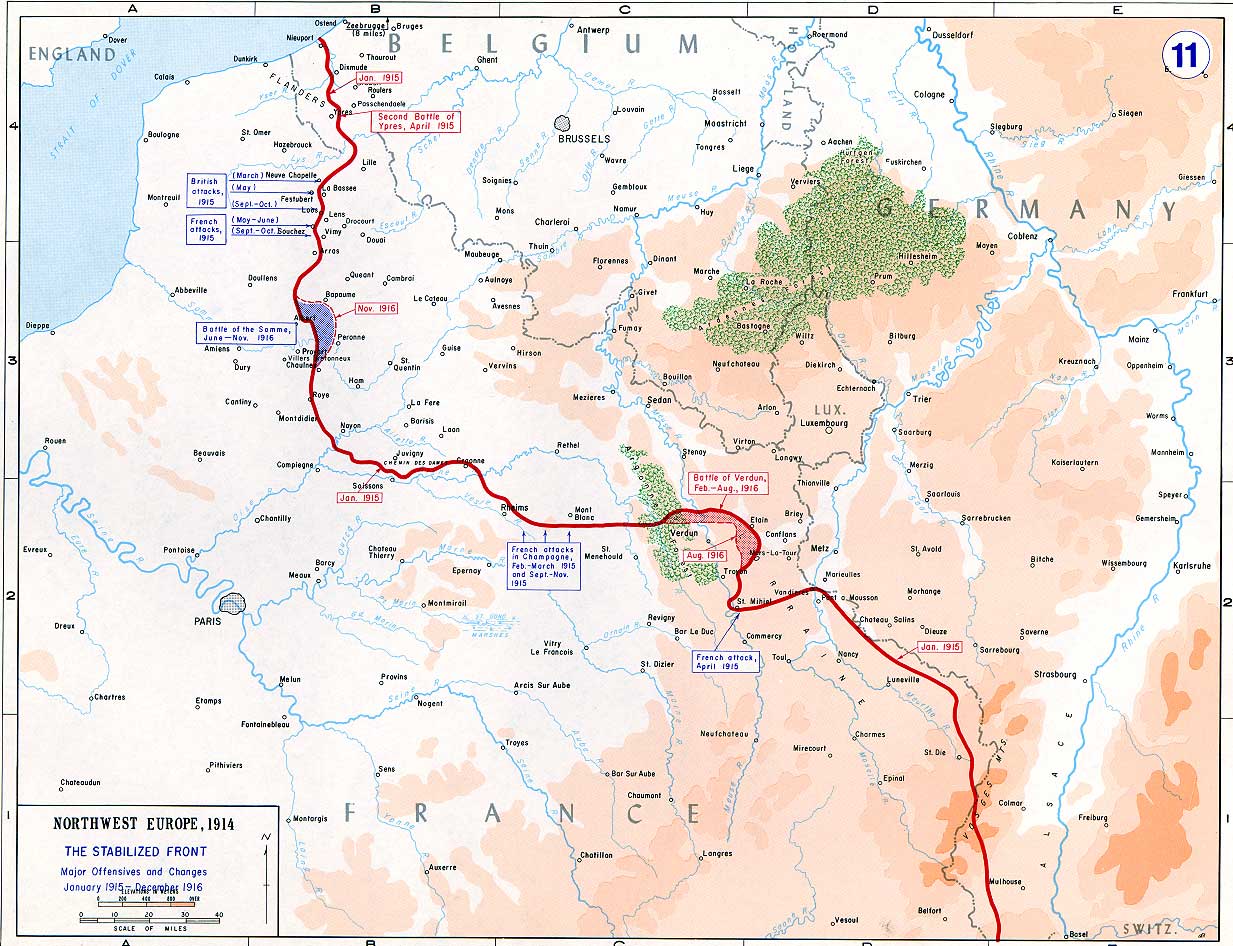

The French and British had committed themselves to an offensive on the Germans at the River Somme in France during Allied discussions at Chantilly, Oise, in December 1915. The idea was for a strategy of combined offensives against the Central Powers in 1916, by the French, Russian, British and Italian armies, with the Somme offensive being a Franco-British contribution to this offensive plan on multiple fronts.

The Chief of the German General Staff, Erich von Falkenhayn, also intended to split the Anglo-French Entente, to open up multiple offensives on the western front during 1916. His wishes were to be fulfilled, the battle of The Somme and the Battle of Verdun would be the largest battles during the war.

When the Imperial German Army began the Battle of Verdun on the Meuse on 21 February 1916, French commanders diverted many of its divisions, largely leaving the Somme to the British.

The first day on the Somme (1 July) saw a serious defeat for the German Second Army, however, it was also the worst day in the history of the British army, which suffered 57,470 casualties.

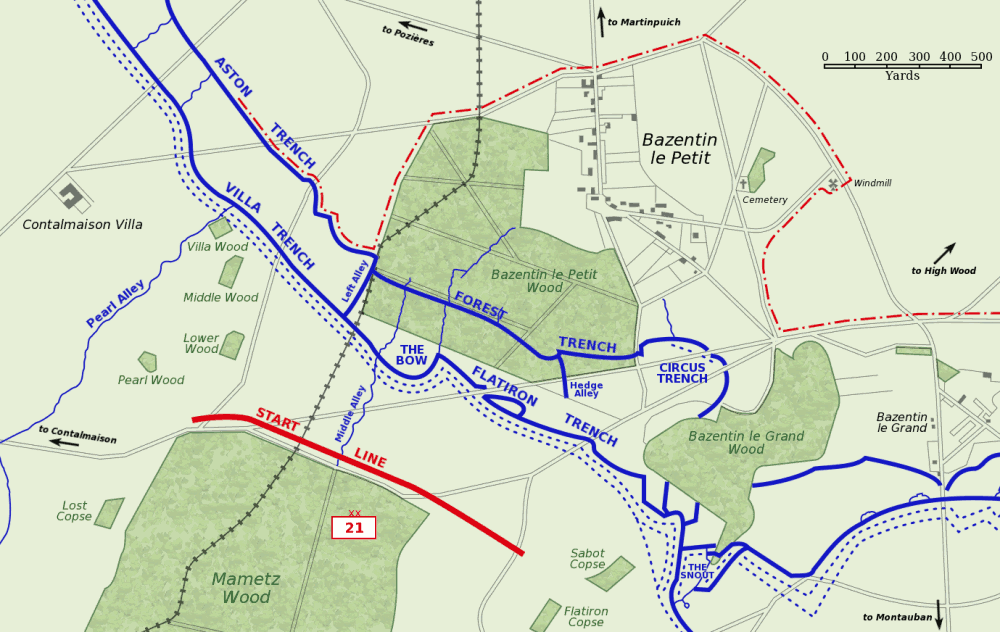

Following the initial success of the battle, Anglo-French forces pressed forward towards the German second line. The attack began on July the 14th from the northwest along the crest of the ridge to Pozières on the Albert–Bapaume road after the artillery bombardment. The attack was successful and the objective was captured.

Another offensive was launched on July 19th by British anglo-french forces to support the Fourth Army on the Somme 80 km (50 mi) to the south, by exploiting a believed weakening of the German defenses. Although the German defense was “gravely” underestimated and the attackers were outnumbered 2:1. This attack was the debut of the Australian Imperial Force on the Western Front. It was according to historian Ross McMullin “the worst 24 hours in Australia’s entire history”. It ended in failure. The attackers lost 7,080 men, of these, 5,533 were incurred by the 5th Australian Division. The Germans lost 1,600–2,000 men.

The British-French forces continued their offensive on multiple locations at around The Somme, at Delville Wood, Pozières, Guillemont, and Ginchy during the autumn of 1916. All of which were successful in achieving their objectives. In the Battle of Ginchy, the 16th Division captured the German-held village, Ginchy, north-east of Guillemont. It was the biggest attack during the Somme offensive and inflicted circa 130,000 casualties on the German defenders during September.

Canadian Corps, New Zealand Division, and tanks of the Heavy Branch of the Machine Gun Corps made their debut in the war at the offensive of Flers–Courcelette in late September, resulting in tactical gains but without achieving a breakthrough of the German defenses.

Two other offensives were launched during late September, The Battle of Morval by the Fourth Army on Morval, Gueudecourt and Lesboeufs held by the German 1st Army and the Battle of Thiepval Ridge launched only 24 hours afterward the Morval offensive. These two offensives would mark the first British use of new techniques in gas warfare, machine-gun bombardment and tank-infantry co-operation.

Three more offensives were launched during October and November, The Battle of Le Transloy, The Battle of the Ancre Heights and the Battle of the Ancre. All of which were largely successful in achieving their objectives. Although none were able to break through the German defenses.

The Somme offensive would prove indecisive. At the end of the battle, British and French forces had only penetrated 10 km (6 mi) into the German-occupied territory. The Anglo-French armies failed to capture the key strategic town of Péronne and halted 5 km (3 mi) from Bapaume, where the German armies maintained their positions over the winter.

The Battle of the Somme is notable for the importance of air power and the first use of the tank. Aircraft and powerful artillery made the destruction of German units in battle worse by a simple fact, a lack of rest; As British and French aircraft and long-range guns reached well behind the front-line, this meant that troops returned to the heat of the battle exhausted.

Enemy superiority is so great that we are not in a position either to fix their forces in position or to prevent them from launching an offensive elsewhere. We just do not have the troops…. We cannot prevail in a second battle of the Somme with our men; they cannot achieve that anymore. (20 January 1917)[54]

— German general Hermann von Kuhl

The Germans would make a scheduled strategic withdraw to the Siegfriedstellung (Hindenburg Line), but debate continues over the real necessity, significance, and effect of the battle.

General Erich von Falkenhayn who succeeded Helmuth von Moltke as Chief of the Oberste Heeresleitung (Chief of the German General Staff), would himself be replaced as Chief of Staff by Paul von Hindenburg.

The Anglo-French battle commanders and leaders were Douglas Haig, Ferdinand Foch, Henry Rawlinson, Émile Fayolle, Hubert Gough and Joseph Alfred Micheler. German commanders and leaders were Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria, Max von Gallwitz and Fritz von Below.

Total casualties are estimated to about 420,000 British and 200,000 French soldiers. With circa 434,000–680,000 German casualties.

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55136/b1b0b614-5b72-486c-901d-ff244549d67a-350x260.webp)

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55124/79bc18fa-f616-4951-856f-cc724ad5d497-350x260.webp)

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55099/2638a982-b4de-4913-8a1c-1479df352bf3-350x260.webp)