The enigmatic peoples of ancient Greece have now received a genetic historical context.

An international research team has gathered archaeological findings and conducted DNA analyses of bones and teeth from 19 different ancient individuals. The results can help us understand more about the origins of the Minoan and Mycenaean cultures and the link between them.

Ancient cultures

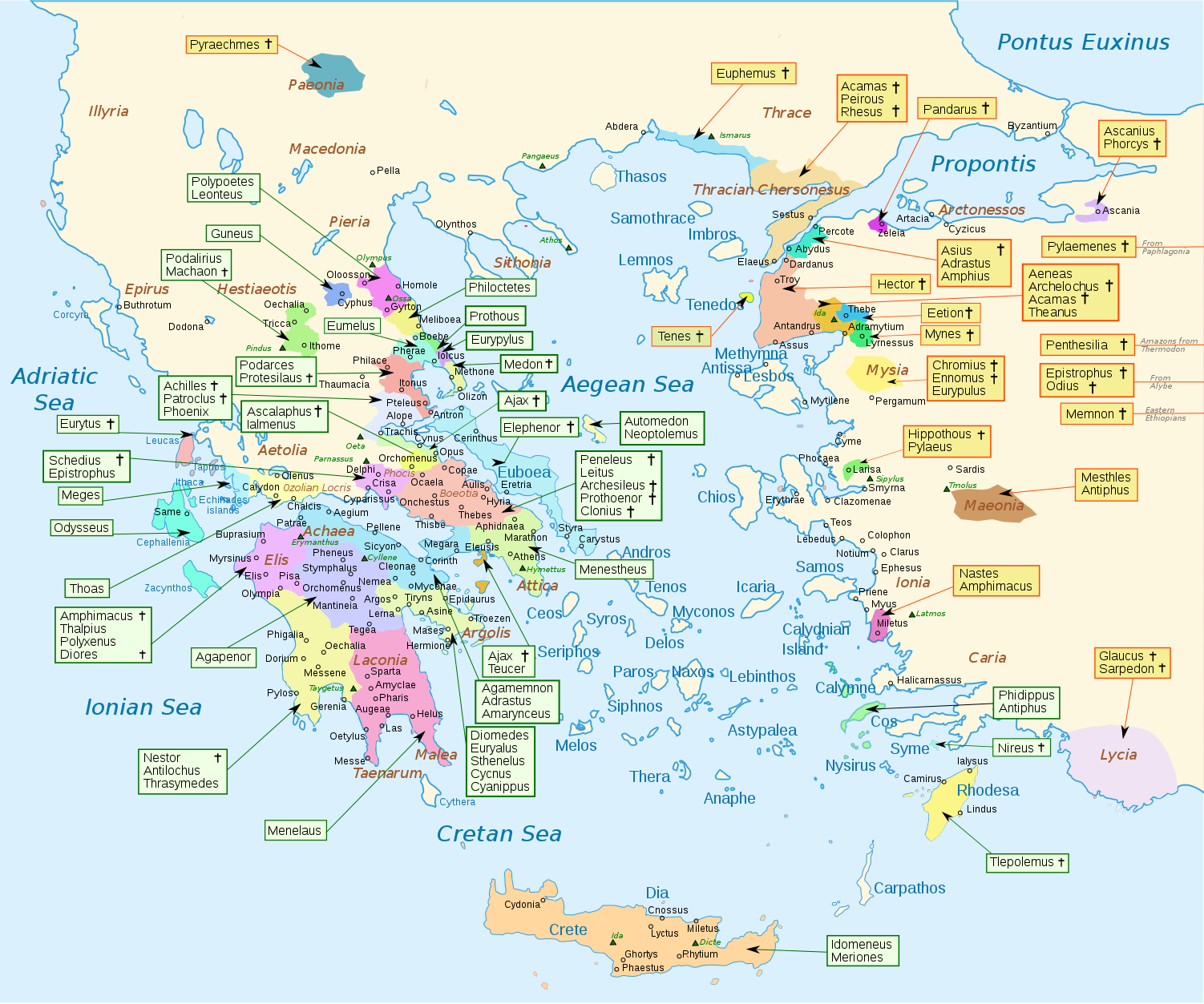

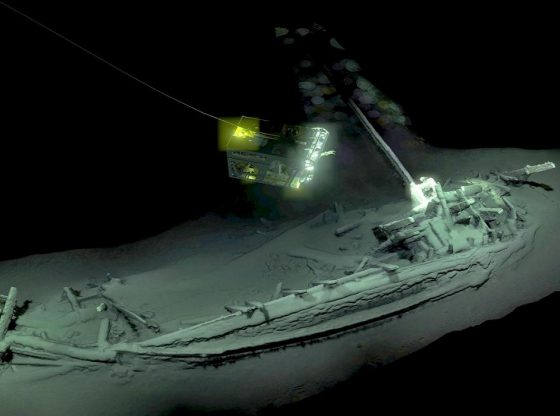

These cultures existed between 3,000 and 5,000 years ago. The Mycenaean civilization (1600 to 1100 BCE) represents the first advanced civilization in mainland Greece, with its palatial states, urban organization and fantastic works of art. The Minoan civilization, a maritime people with sophisticated palaces, flourished on the island of Crete and other Aegean islands about 2600 to 1100 BCE.

Both cultures were literate and had written a language, passing down written sources of contemporary descriptions of everyday life, philosophy, and art, however, the Minoan written language (‘Linear A’) is yet to be deciphered.

With such famous stories such as the Minotaur that dwelt at the center of a labyrinth designed by the architect Daedalus and his son Icarus, on the command of King Minos of Crete. The story about King Agamemnon who led the Greeks in the Trojan war that Homeros wrote about in the Iliad.

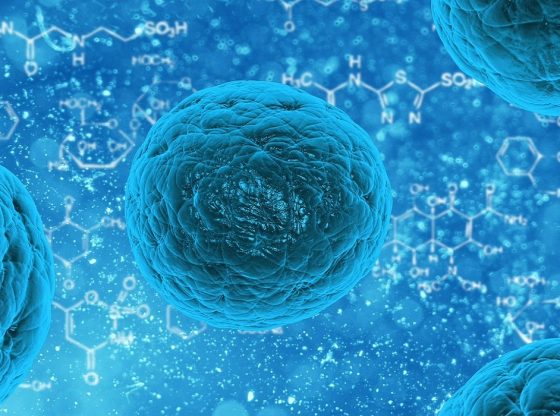

Genetic analysis

Researchers from the Max Planck Institute in Germany, from the University of Washington, teamed up with Greek and Turkish archeologists and anthropologists to obtain samples from 19 Bronze Age individuals excavated from tombs and other sites throughout the Aegean.

They extracted ancient DNA from 10 Minoans, four Mycenaeans, three individuals from southwest Anatolia (Turkey), one individual from Crete, who dates from after the arrival of the Mycenaeans on the island, and one Neolithic sample (5,400 BCE) from the mainland that predated the emergence of the Greek civilizations.

The researchers then compared and contrasted the DNA samples with previously reported data from 332 other ancient individuals in Europe, 2,614 present-day humans, and two present-day Cretans.

According to the genetic analyses, the Minoans and Mycenaeans were very closely related, but with some differences that made them distinct from each other. Both the Bronze Age Minoans and Mycenaeans, as well as their neighbors in Bronze Age Anatolia, derived most of their ancestry from a Neolithic Anatolian population, and a smaller component from farther east, related to populations in the Caucasus and Iran.

Revealing a genetic continuity in the Aegean from the time of the first farmers to present-day Greece, but with some admixture with Ancient North Eurasians and peoples of the Eastern European steppe both before and after the time of the Minoans and Mycenaeans.

The Mycenaeans have some ancestry distinct from the Minoans and details regarding this “northern” DNA ancestry remains to be worked out, to establish whether that contribution came from a single rapid migration or sporadic waves over a long period. It may provide the missing link between Greek speakers and their linguistic relatives elsewhere in Europe and Asia.

While not identical to the Bronze Age populations, modern Greeks are genetically closely related to the Mycenaeans. Modern Greeks also show some additional admixture with other groups and a corresponding decrease in heritage from the Neolithic Anatolians. This suggests that there has been a large degree of population continuity in Greece, but it has not been isolated.

Reference:

Iosif Lazaridis et al. Genetic origins of the Minoans and Mycenaeans. Nature August 2, 2017. DOI: 10.1038 / nature23310

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55136/b1b0b614-5b72-486c-901d-ff244549d67a-350x260.webp)

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55124/79bc18fa-f616-4951-856f-cc724ad5d497-350x260.webp)

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55099/2638a982-b4de-4913-8a1c-1479df352bf3-350x260.webp)