It has long been known that physical activity counteracts many of the negative effects of brain aging, but now researchers in California may have found another cause as to why this is.

The research team has found a new mechanism for how exercise can affect memory. It is one of only a few studies that have actually been able to show the detailed mechanism.

The researchers studied aging mice, which they divided into a physically active group and a sedentary group. In the mice that were allowed to train, the memory improved, with new nerve cells formed in the brain. By transferring blood plasma from the active to the sedentary mice, they also got better memory.

The scientists discovered that post-exercise, Gpld1 – a protein produced in the liver – was increasingly expressed in the blood circulation of the mice. The amount of Gpld1 correlated with improvements in the animal’s cognitive performance assessed by a radial arm water maze test (RAWM) and contextual fear conditioning behavioral tests.

Physical activity increases the liver’s production of Gpld1. The researchers then show that the same effect on memory can be achieved by increasing the production of the protein artificially. The team adopted genetic engineering to evoke the overproduction of Gpld1 in the livers of aged mice.

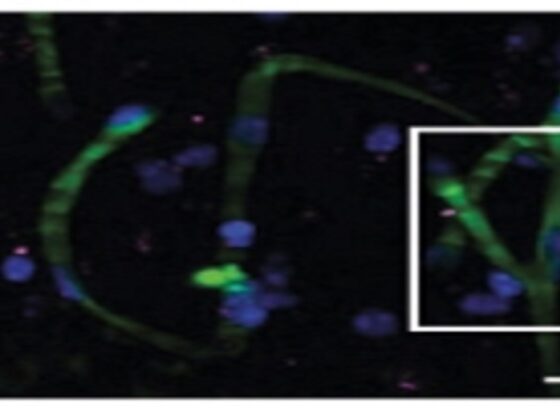

The aged animals overexpressing Gpld1 were found to commit significantly fewer errors when locating the target platform in RAWM training compared to controls and performed better overall. In parallel, analyses of the mice’s brains revealed increased neurogenesis in the hippocampus.

But the team does not yet know why this effect occurs, yet. What exactly happens in the brain is unclear and whether it is possible to translate the findings from mice to people is also unclear and in need of evaluation. We do know that cleavages of Gpld1 substrates are implicated in signaling cascades linked to blood coagulation and inflammation.

The team hypothesizes that Gpld1 might be eliciting some form of reversal effect on inflammation and blood coagulation that are elevated in aging individuals and are linked to cognitive decline.

The findings could feasibly lead to new therapies that confer the neuroprotective effects of physical activity on people who can’t exercise due to physical limitations.

“If there were a drug that produced the same brain benefits as exercise, everyone would be taking it,”

“Now our study suggests that at least some of these benefits might one day be available in pill form.”

– Saul Villeda, PhD, a UCSF assistant professor in the departments of anatomy and of physical therapy and rehabilitation science. Villeda is the senior author of the team’s published paper in Science.

Exercise is one of the best-studied and most powerful ways of protecting the brain from age-related cognitive decline. Exercise has been shown to improve cognition in individuals at risk of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and frontotemporal dementia, even for individuals who carry rare gene variants that inevitably lead to dementia.

Reference:

Horowitz, A.M. et al. “Blood factors transfer beneficial effects of exercise on neurogenesis and cognition to the aged brain”. Science, 10 juli 2020. Doi: 10.1126/science.aaw2622

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55136/b1b0b614-5b72-486c-901d-ff244549d67a-350x260.webp)

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55124/79bc18fa-f616-4951-856f-cc724ad5d497-350x260.webp)

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55099/2638a982-b4de-4913-8a1c-1479df352bf3-350x260.webp)