A 26-year-old woman with an aggressive form of brain cancer has been given new hope after being treated with the malaria medicine chloroquine. Now scientists want to test the medicine on a larger group of patients.

“You have less than twelve months to live.”

This was what Lisa Rosendahl was told when she received the doctor’s prognosis one and a half years ago shortly afterward having discovered a tumor in her brain that had become resistant to both chemotherapy and other cancer treatments.

But thanks to an experimental effort using the drug called chloroquine, which is normally used to treat malaria, the researchers at the University of Colorado in the United States managed to make Lisa’s tumor susceptible to treatment.

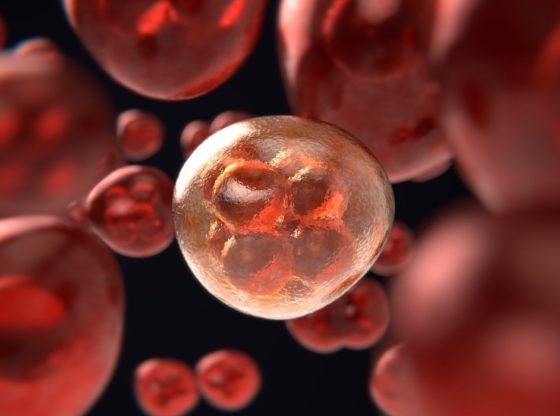

Lisa Rosendahl is suffering from an aggressive form of brain cancer called glioblastoma. This type of cancer has the ability to resist cancer drugs. It relies on self-cannibalism called autophagy, in which cancer cells eat their own dead cells to make way for new cancer cells. This may ultimately lead to that cancer cells becomes immune to, for example, chemotherapy.

Autophagy is a normal process inside by which dead or damaged cells are removed and recycled to make way for new replacement cells. Taken from Greek, the term literally means “to eat oneself”, and it’s an important way of detoxifying and repairing the body.

The malaria medicine chloroquine is known to inhibit autophagy and with that knowledge in mind, the researchers decided to treat Lisa Rosendahl with a mixture of chloroquine and the cancer medicine called vemurafenib.

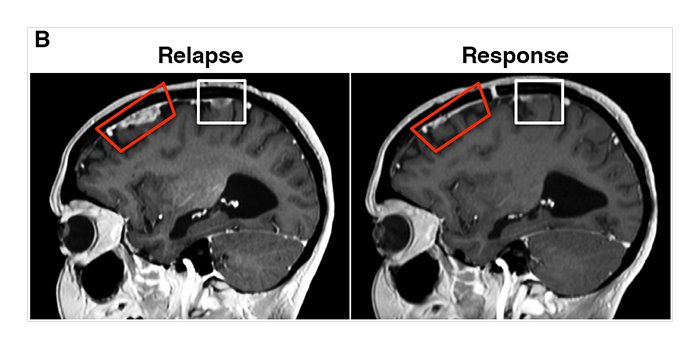

Vemurafenib had previously been used to push Lisa’s cancer past the tipping point of survival but then the cancer learned to use autophagy to pull itself back from the brink. Now with chloroquine nixing autophagy, vemurafenib started working again. Chloroquine effectively weakened the cancer’s defenses enough to get the vemurafenib drug working again.

“Miraculously, [Rosendahl] had a response to this combination,” “Four weeks later, she could stand and had improved use of her arms, legs, and hands.” said Jean Mulcahy-Levy, one of the researchers.

Together with her colleagues, Mulcahy-Levy have tried the therapy on two other cancer patients with successful results and the scientists now hope to do a larger clinical trial that explores the use of autophagy inhibition drugs on glioblastoma and beyond only BRAF+ cancers.

Since chloroquine has already earned FDA approval as a safe and effective (and inexpensive) treatment for malaria, the paper points out that it should be possible to “quickly test” the effectiveness of adding autophagy inhibition to a larger sample of cancer types.

Reference:

Jean M Mulcahy Levy Shadi Zahedi Andrea M Griesinger Andrew Morin et al. Autophagy inhibition overcomes multiple mechanisms of resistance to BRAF inhibition in brain tumors DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7554/eLife.19671

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55136/b1b0b614-5b72-486c-901d-ff244549d67a-350x260.webp)

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55124/79bc18fa-f616-4951-856f-cc724ad5d497-350x260.webp)

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55099/2638a982-b4de-4913-8a1c-1479df352bf3-350x260.webp)