The arctic region could be almost completely ice-free during summer in 20 years already, researchers warn in new report.

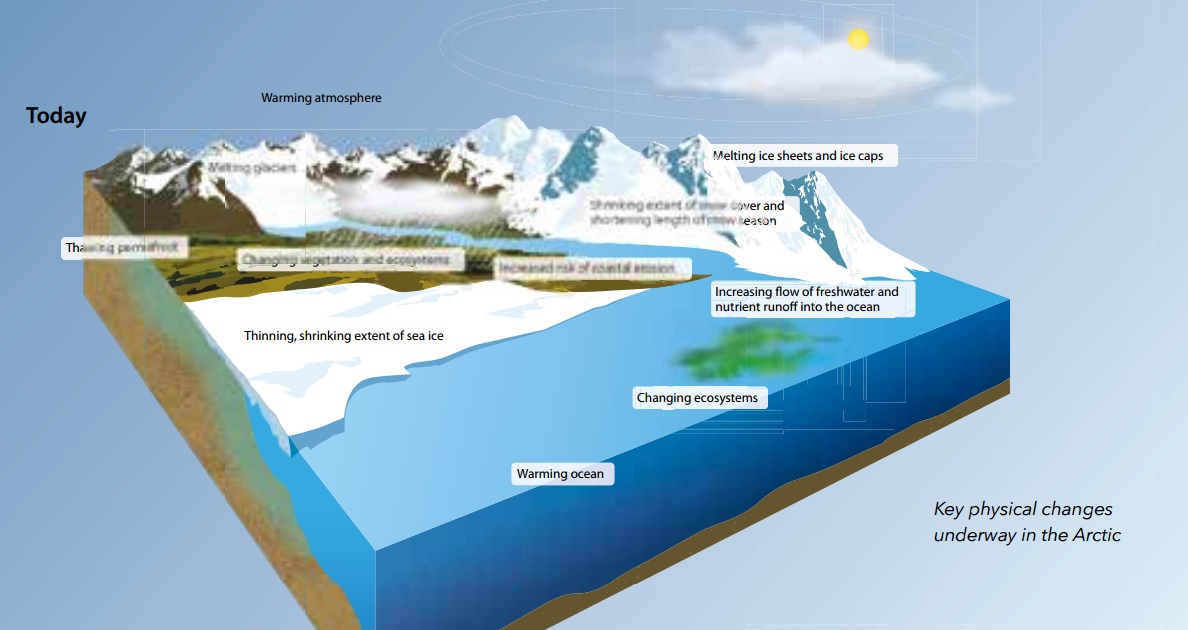

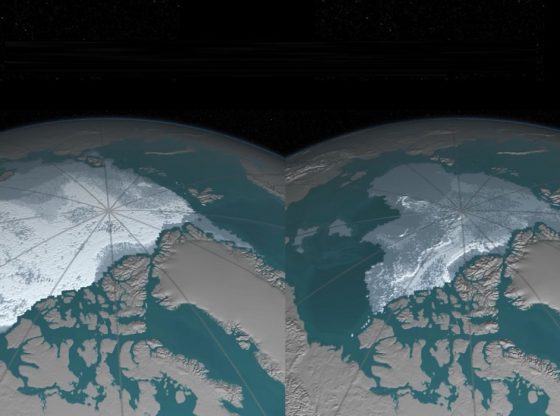

The temperature is changing more than twice as fast in the arctic compared to the rest of the world. The ice around the North Pole is decreasing with each passing year.

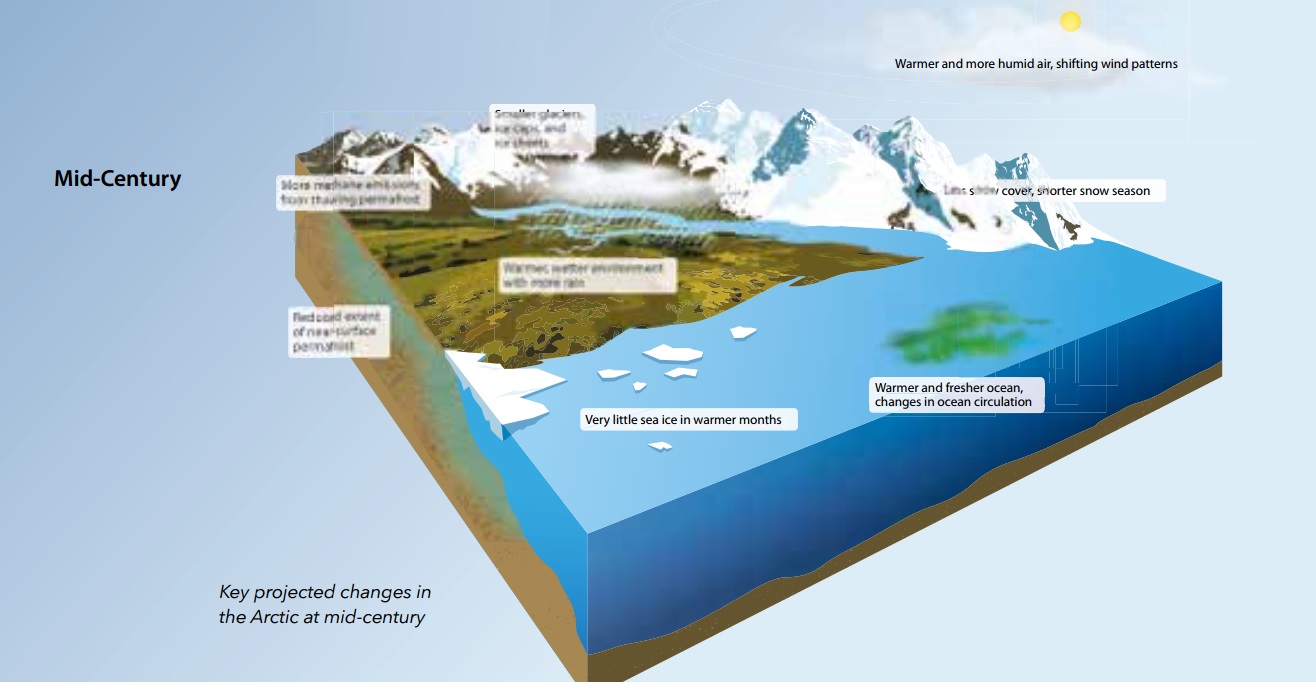

Researchers are now sounding the alarm that the arctic region will be essentially ice-free during the summer in 20 years already.

This is more than 10 years earlier than the UN Climate Panel has estimated and is the conclusion by the Arctic Council, with over 90 researchers involved from several countries, who have analyzed the accelerating changes seen in the arctic.

The report The Snow, Water, Ice and Permafrost in the Arctic (SWIPA) assessment is a periodic update to the Arctic Climate Impact Assessment. The first SWIPA assessment was conducted between 2008 and 2010, and was published in 2011.

The ice is getting thinner, the report concludes. Between 1975 and 2012, the thickness decreased by 65 percent and thick ice that survives the summers is becoming increasingly rare. More open water speeds up the warming by reflecting less sunlight.

The habitat for polar bears, seals, and walruses’ shrinks. Other species will probably move northwards, claiming new lands.

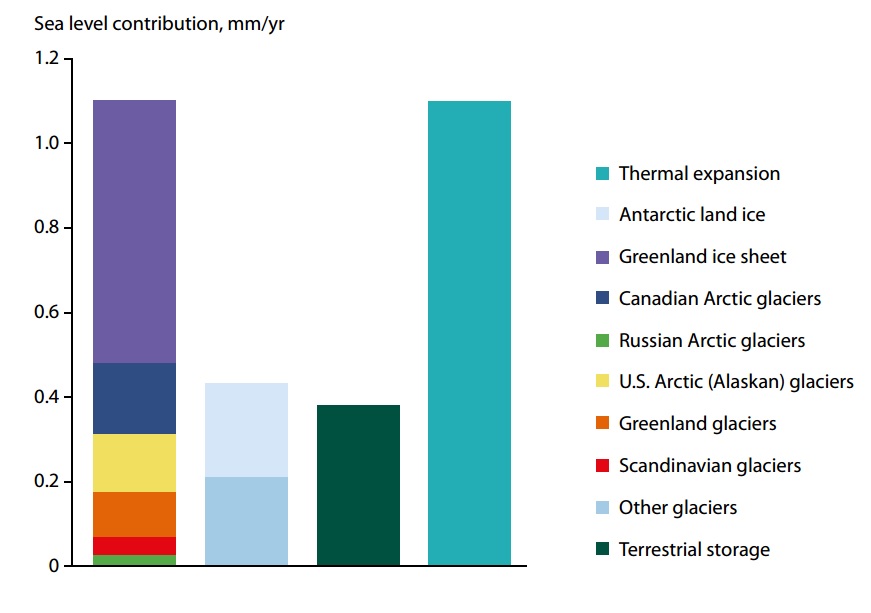

Greenland ice and glaciers have melted twice as fast in recent years. Between 2011 and 2014, a volume equivalent to a massive ice block measuring 7.5 kilometers has disappeared. This is twice as much ice compared to 2003-2008.

The melting ice on Greenland has already pushed the sea level to rise a centimeter. But the ever faster thaw will cause the oceans to rise by another 25 centimeters in addition to 0.5-1 meters as the UN climate panel said.

The researchers warn that it will be 12 degrees warmer than today in the Arctic by the end of the century if carbon dioxide emissions continue as today. If emissions fall sharply, in line with the Paris agreement limiting global temperatures to rise 1.5-2 degrees, the temperature in the Arctic will rise by 6 degrees.

Climate models project future conditions, based on scenarios. But what does that mean? Scenarios depict a range of plausible alternative futures, based on assumptions about future economic, social, technological, and environmental conditions that drive greenhouse gas emissions and their concentrations in the atmosphere. Climate modelers use these scenarios to project, rather than predict, future climate under each scenario. Projections answer the question: if emissions and concentrations were to proceed along this pathway, what changes in climate would result? SWIPA 2017 compared the outcomes of two different greenhouse gas concentration scenarios, RCP-4.5 and RCP-8.5. In the RCP-4.5 scenario, reductions in emissions lead to stabilization of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere by 2100 and a stabilized end-of-century global average temperature rise of 1.7–3.1°C above pre-industrial levels. RCP-8.5 is a high-emission business-asusual scenario, leading to a global nonstabilized temperature rise of 3.8–6°C by 2100.

Reference:

AMAP, 2017. Snow, Water, Ice and Permafrost. Summary for Policy-makers. Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP)

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55136/b1b0b614-5b72-486c-901d-ff244549d67a-350x260.webp)

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55124/79bc18fa-f616-4951-856f-cc724ad5d497-350x260.webp)

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55099/2638a982-b4de-4913-8a1c-1479df352bf3-350x260.webp)