Ocean acidification is the ongoing decrease in the pH of the Earth’s oceans, caused by the uptake of carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere. Researchers now show that corals may be better equipped for acidification than previously thought.

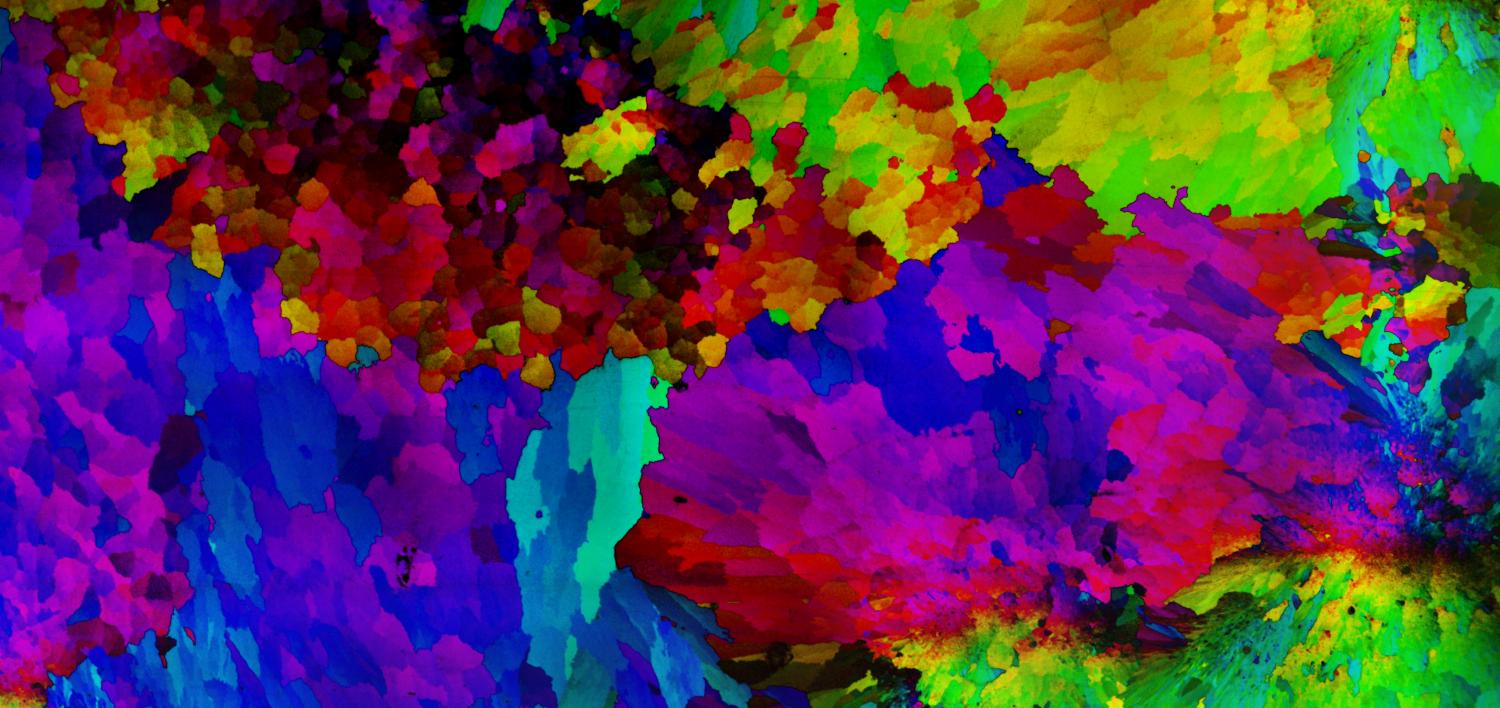

The researchers from the University of Wisconsin-Madison investigated how the coral ‘Stylophora pistillata’ builds its coral skeleton of calcium carbonate.

It turned out that the coral partly builds up the skeleton’s minerals inside its tissue, protected from the sea, and partly in a faster way than previously known.

Together, this would mean that this species, and perhaps also other corals, has some ability to cope with acidification.

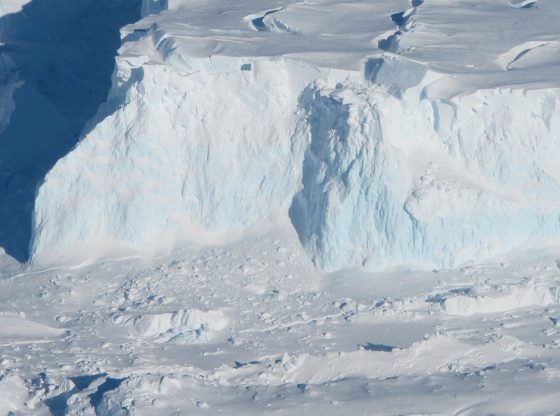

Corals are affected by warming-induced bleaching and postmortem dissolution, but the finding here that ACC particles are formed inside tissue may make coral skeleton formation less susceptible to ocean acidification than previously assumed.

This new research indicates an active role for corals in developing their skeletons and suggests that they are not entirely at the mercy of the ocean’s changing chemical makeup.

Reference:

Gilbert et al. “Amorphous calcium carbonate particles form coral skeletons“. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, August 2017. www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1707890114.

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55136/b1b0b614-5b72-486c-901d-ff244549d67a-350x260.webp)

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55124/79bc18fa-f616-4951-856f-cc724ad5d497-350x260.webp)

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55099/2638a982-b4de-4913-8a1c-1479df352bf3-350x260.webp)