There is certainly some mistrust in the West regarding China’s rise as a global economic superpower, that jobs leave to not return, that factories and innovation are pulled to China as the gravity of economic opportunities leaves behind a vacuum in the western world. But without the rapid economic growth we have seen in China during the past 30 years, would the rest of the world be better or worse off?

As economic models predict, the future trade patterns will reverse to reach a new equilibrium at a higher level of prosperity, both within China and the rest of the world. As trade by itself is a prerequisite for global economic growth via comparative advantage and the spreading of innovation.

But is this accurate? How does the rise of China affect Future jobs in the West (intra-industry trade)? And how does trade drive growth via comparative advantage and innovation?

History of Trade: Silk Road

Trade has been an essential part of the human development and to raise overall prosperity. To facilitate the creation of new markets and allow for interaction between people to exchange ideas, to promote innovation, science, and technology.

The silk road between the East and West did not only bring goods from one corner of the world to another, it allowed for the exchange of ideas.

As economic and political exchange between the East and West flourished, so did many religious ideas, as they spread and were introduced in China; Buddhism, Zoroastrianism, Manicheism, Nestorianism, and Islam.

Chinese inventions and technologies of papermaking, printing with movable type, gunpowder, and the compass were transmitted to the West.

Silk spinning was a long-held and well-kept secret of the Chinese. This fact probably increased the demand for the fabric in the West. Chinese porcelains and lacquers were much sought for in and traded to the West as well.

But the trading of goods most certainly went both ways, with a large number of products of the West that flowed into China. Such as grapes, clover, walnuts, carrots, peppers, beans, spinach, cucumbers, pomegranates, rare animals, medicinal materials, flavorings, and jewelry.

As the Muslim world was a trade hub in between the West and the Far East, it could both allow and disallow trade within its territory, but it also provided the world of ideas of mathematics, both refined by Arab mathematicians, as guardians of ideas from the ancient world. But also to trade goods of their own, such as citrus fruits, dates, and coffee.

History of Trade: The New World

When Columbus’ first set foot in the Americas, this is a pivotal event in all of human history. As two great populations of humanity that had been separated since the Ice Age – developed in isolation for over 15,000 years – were reunited. Prior to the event of Europeans settling in the New World, these two great world zones have largely existed in isolation. But by crossing the Atlantic, Columbus opens up the vast American continents and the millions of people living there to the rest of the world.

As Europeans discovered and settled on the American continents, this constituted a complete change in food and animal dispersal across the globe. Giving rise to not only increased global trade but also to allow for increased population and economic growth.

As American crops, animals and food spread to the rest of the world to be cultivated. Asian, African and European crops and animals were introduced to the American continents. Potatoes provided the principal energy source for the Inca Empire and were to become a staple food in Europe. Horses had not been seen in North America for 12,000 years, were to be returned to the Americas with Christopher Columbus in 1493.

The old world of Europe, Asia, and Africa – now reached across the Atlantic to create a vast new global network.

World trade has ever since been essential for global economic development.

Everyone Gains: Comparative Advantage

The economic theory of comparative advantage refers to the ability of a person or a country to produce a particular good or service at a lower marginal and opportunity cost over another. Even if a country is more efficient to produce all goods (absolute advantage) compared to another country, both countries will still gain by trading with each other, as long as they have different relative efficiencies.

Comparative Advantage: The Long Version

To illustrate the gains from specialization and trade, we shall consider a two-country and a two-commodity scenario. The figure below depicts the production possibilities curve between autos and textiles for Japan and Mexico.

Japan produces 100 autos for 50 textiles, that is, Japans marginal cost for producing 1 textile is 2 cars. Mexico produces 45 autos for 90 textiles, that is, Mexico’s marginal cost for producing 1 textile is 0,5 cars. Japan is relatively more efficient in producing cars, and Mexico is relatively more efficient at producing textiles.

This curve shows the maximum combinations of autos and textiles that can be produced by each nation. Thus, Japan can produce 100 autos and 0 textiles per week, or 50 textiles and 0 autos per week, or any other combination that lies along the production possibility curve. One example of an intermediate combination feasible for Japan is 60 autos and 20 textiles. Similarly, Mexico can produce 45 autos and 0 textiles per week, or 0 autos and 90 textiles per week, or any other combination that lies along Mexico’s production possibility curve.

No trade

Let us suppose that Japan and Mexico initially do not trade with one another. Let us further assume that Japan is initially producing (and thus consuming) at point A, that is, 60 autos and 20 textiles. We also suppose that Mexico is initially producing at point B, yielding 15 autos and 60 textiles. Thus, auto production is 75 (= 60 + 15) per week, while textile production is 80 (= 20 + 60) per week.

In this initial equilibrium, Japan and Mexico are each self-sufficient, which is to say that each country produces exactly what it consumes, and thus does not have to rely on any other country for anything.

Specialization

Let us suppose that the two countries then agree to alter their production patterns so as to specialize in producing the good in which each has the lower cost of production for, they are marginally better at producing and a higher productivity for. A situation defined as a comparative advantage.

Each country will produce only one good and then trade.

Japan is marginally better at producing autos at a lower cost. We assume that Japan agrees to produce only autos, resulting in a total auto production of 100 per week.

Similarly, we assume that Mexico produces only textiles, which is a good for which they have a comparative advantage. Thus, total production of textiles is 90 per week.

There are two key features of this hypothetical arrangement.

First, when the countries specialize in producing the goods in which they have a comparative advantage, the output of both goods rises: Total auto production goes from 75 per week to 100 per week, while textile production rises from 80 per week to 90 per week.

The second is that neither country’s consumers want to consume all of its own output that results from specialization. Japan originally had the choice of producing and consuming 90 autos and 0 textiles, or 60 and 20, and it chooses the latter. Hence it must prefer to consume the bundle (60, 20) rather than the bundle (90, 0). Similarly, Mexico’s consumers could have picked the bundle (0, 90) when it was self-sufficient, but did not, instead it chose the combination (15, 60), implying that it preferred this bundle.

In a more general sense that is actually observed in the real world, countries end up producing a variety of goods and more than one country typically produces any given trade good. Nevertheless, even if total specialization is not implemented, there is still some specialization.

Trade is the solution

Clearly, the two countries face a dilemma. If they specialize, they can produce more of both goods. But if they specialize they cannot satisfy their consumers. So what are they to do? The simple answer is an exchange.

If asked to sell some of the cars it produces, it is clear that Japan would not accept less than 0.5 textiles for every auto, because this is what it could produce on its own. Mexico would not offer more than 2 textiles for every auto because this is the cost at which it could produce autos on its own.

With trade, a mutually acceptable price ratio would emerge somewhere between 0.5 textiles per auto and 2 textiles per auto. To be specific, let us suppose that the price on which the two countries agree to trade is 1:1, that is, one car per textile. Let us further assume that at that price ratio, Japan is willing to sell (and Mexico is willing to purchase) exactly 25 autos.

Thus, Japan produces 100 cars and sells 25 of them to Mexico in return for 25 textiles. This enables Japan to consume at the point C, that is, 75 autos and 25 textiles. The other half of this arrangement is that Mexico produces 90 textiles and sells 25 of them to Japan in return for 25 autos. This enables Mexico to consume at point D, that is, 25 autos and 65 textiles.

Higher productivity

When countries are self-sufficient, their consumption possibilities are limited by their production possibilities. But notice what happens when specialization and exchange take place: Both countries are actually able to consume bundles that lie beyond their own production possibilities’ curve.

For Japan, bundle C implies more of both autos and textiles. Which is also true for Mexico, with bundle D that means more of both autos and textiles compared to if no trade was allowed.

It is worth emphasizing that it is only the possibility of exchange that allows these (and other) nations to take advantage of specialization. In the self-sufficient state, points A and B are chosen by the nations as they prefer these allocations as consumption bundles.

Absent the possibility of trade, the optimal production bundles {(100, 0); (0, 90)} would never have been chosen since neither country prefers them as consumption bundles. Thus, because exchange permits the choice of higher-output production bundles, we can conclude that trade is productive. It enables the participants to consume more than what would otherwise be possible.

Comparative advantage: The short version:

Two men live alone on an isolated island. To survive they must undertake a few basic economic activities like water carrying, fishing, cooking and shelter construction, and maintenance.

One guy (let’s call him Adam) is young, strong, and educated. He is also faster, better, and more productive at everything compared to the other guy. He has an absolute advantage in all activities.

The other guy, let’s call him Tony, is old, weak, and uneducated. He has an absolute disadvantage in all economic activities.

For some activities, the difference between the two is great, in others, much smaller.

Despite the fact that the younger man has an absolute advantage in all activities, it is not in the interest of either of them to work in isolation since they both actually benefit from specialization and exchange.

If the two men divide the work according to comparative advantage then young Adam will specialize in tasks at which he is most productive, while Tony will concentrate on tasks for which his productivity is the highest. Such an arrangement will increase total production for any given amount of labor supplied by both men and it will benefit both of them.

Inter/intra-industry trade

via chartsbin.com

The relative cost advantage is what drives comparative advantage. This type of trade is defined as inter-industry trade. Trade with different goods for which each country has a different productivity level. This productivity level is determined by capital, labor, and technology.

![]()

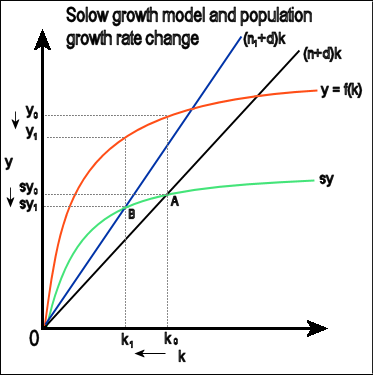

With increasing trade and economic growth, China invests this surplus in capital and also harness benefits by increased innovation. The Solow model Y=AKL (A-innovation/technology, K-capital, and L-labor) shows what happens. With this increased capital accumulation and innovation, the average productivity of labor increases.

This, in turn, implies that with increased growth in China, increased marginal productivity of labor raises real wages. And with higher real wages, the cost advantage of production in China dissipates.

Hence, trade patterns reverse. China substitutes inter-industry trade for intra-industry trade. This is a trade pattern with similar products; products similar in their production intensity. Such as the trade pattern seen between European nations. With Germany exporting BMW or Audi cars to Sweden and Sweden exporting ABB industrial robots or Scania lumber trucks to Germany.

The trade reaches a new equilibrium, of higher overall production, higher overall consumption, more efficiency.

Innovation

Economic research at the University of California Berkley shows that not only does innovation drive growth. Or that innovation (the variable “A” in the Solow model) is the engine of long-term economic growth. But also that all innovation, in all countries contribute to the overall global stock of ideas and give rise to higher growth in all countries. That is, with increased growth in China, increased innovation in China, everyone gains.

It is ambiguous however to speculate in how the future trade patterns will emerge since when future companies search for advantages in production and perhaps Africa appears as a viable alternative for low-cost production, there is also a simultaneous development into more advanced and cheaper industrial robotics with the risk of technological unemployment. This is a fact that most certainly will impact how industry adapts to new technological endowments. Not to mention other variables such as a changing environment, global warming and the risk of conflicts.

______________________________

The Role of History in Bilateral Trade Flows

A Globalization Puzzle

_______________

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55124/79bc18fa-f616-4951-856f-cc724ad5d497-560x416.webp)

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55099/2638a982-b4de-4913-8a1c-1479df352bf3-560x416.webp)

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55136/b1b0b614-5b72-486c-901d-ff244549d67a-350x260.webp)

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55124/79bc18fa-f616-4951-856f-cc724ad5d497-350x260.webp)

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55099/2638a982-b4de-4913-8a1c-1479df352bf3-350x260.webp)