This is a three-part series summarizing human existence from hunter-gatherers to civilization to the modern world we see today.

Wealth of Nations

The story of civilization is truly interdisciplinary at its heart, as we move from historical and archaeological evidence in part one. To explanatory via geography, biology, and geology in part two. We now move forward to modern history, where economics is central, so is the social science, law and indeed statistics.

When Geography Fails: The Complexity of Divergence Commence

Humans went from a nomadic life to a life in settlements and this transposition would ultimately spread across the globe in various pace and fashion. The American continents were cut off from the rest of the developed world and were reached far later in human history during the age of globalization in the 15th century.

Jarred Diamonds Guns Germs and Steel provides us with insight into early human civilization building and broadly answers the question to why certain geographical areas were reached by civilization earlier and became more successful compared to other regions.

Why especially three general areas and their surrounding lands at the Fertile Crescent, China and India/Pakistan were particularly successful in developing agriculture and the domestication of animals. Both of these very much prerequisites for later human stationary society.

Diamond argues that all three areas were naturally well endowed with both eatable plants and animals and they got a head start in the development for this reason. He argues that these endowments also provided these areas and the surrounding lands, Europe and Asia a head start, that made them more mature in issues related to science and technology etc.

This head start was the main reason to why civilizations in these parts were superior to others even later in history. The theory presented by Jarred Diamond, however, fails to explain why some civilizations and nations within these blessed lands later came to diverge in prosperity and development.

China, India, and The Middle East with surrounding lands surpassed western Europe in many areas relating to science and society, with rich contributions to literature, mathematics, and the arts. But later, Europe came to rapidly advance from the late middle ages, with the Renaissance, during the Age of Discovery, Age of Enlightenment and the Scientific Revolution. Europe surpassed China, India, and the Middle East in both overall prosperity and development.

When comparing proximity factors to prosperity related areas such as food production and real wages, Europe far surpassed other agricultural societies. European technology and science were not only more advanced, the progression of technological development and knowledge was far greater than arguably anytime in before in human history.

So why then did Europe surpass the rest of the world in overall prosperity and science knowledge? When the Middle East, China, Japan, and India were provided with the same initial natural endowments. Why did the industrial revolution take place in England and not across the channel, in France or Germany? Why is South Korea more prosperous than North Korea? Why did some former European colonies develop more successfully than others? Such as North America and Australia compared to South America and Africa.

Among countries colonized by European powers during the past 500 years, those that were relatively rich in 1500 are now poor. Mughal India, the Aztecs, and Incas in the Americas were among the richest civilizations in the 1500s, while civilizations in North America, New Zealand, and Australia were less developed. Later, the situation had totally reversed.

Many answers to this conundrum have been suggested throughout history, answers with as varied explanations as they also representative for their time of suggestion, based on both real science and quasi-science. We will examine a couple of these explanations and then focus on the English and North American experiment.

Cause and effect

Mcneill and Hanson

The professor and historian J. R. McNeill complements Jared Diamonds theory on a broad notion but also believes that Jarred has oversold geography as an explanation for later periods in history. Victor Davis Hanson has lifted the notion of certain European politics factors as essential, those being political freedom, capitalism, individualism, republicanism, and rationalism.

Niall Ferguson

The economic historian Niall Ferguson offers insights in the historic success story of Europe in his book “Civilization: Is the West History?”. Where he presents his so-called “killer applications” named to the appreciation and taste of a younger audience. Niall argues that these factors all contributed to the European success.

- Competition – Between countries in Europe and within, between companies.

- Science – A social model (scientific model) making respective countries better at adapting and developing science, with correlation to competition.

- Property – Property and its effect on individual rights, the rule of law and representative government.

- Medicine – Positive effects on demographics, with correlation to science.

- Consumerism – Capitalism and incentives.

- Work ethic – As Max Weber famously linked it to Protestantism, but as Ferguson argues, more linked to capitalism and a general spirit of incentives than any specific cultural aspect.

Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson: Wealth of Nations

The economists Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson argue that a nation’s economic success is predominantly determined by its institutions. In their book, Why Nations Fail these institutions are the determinate factors to why some nations fail and others prosper. In Why Nations Fail they argue that these institutions can explain all aspects of prosperity difference between nations. And using data on among other things, urbanization and population density as a proxy for economic prosperity – Acemoglu and Robinson first dismiss other suggested explanations before presenting their own.

The Geography Hypothesis

Acemoglu and Robinson argue that although Diamond’s thesis is a powerful approach to the puzzle on which he focuses, it cannot be extended to explain modern world inequality. For example, among countries colonized by European powers during the past 500 years, those that were relatively rich in 1500 are now poor. For example, Mughal India and the Aztecs and Incas in the Americas were among the richest civilizations in 1500, while the civilizations in North America, New Zealand, and Australia were less developed. Today the situation is reversed. Neither can it explain the diverse paths taken by for example North and South Korea, or West and East Germany, North and South America etc.

The Culture Hypothesis

This hypothesis stresses the role of culture, beliefs, values, ethics, and religion. Such as the Protestant work ethic first proposed by Max Weber in 1905. Religious devotion, Weber argues; “is usually accompanied by a rejection of worldly affairs, including the pursuit of wealth and possessions”. That those protestant countries in Europe being more successful in capitalism practices is not only a correlation but also causation. Daron and James are dismissive but note that some aspects of culture such as trust are important but trust is an outcome of institutions, not a cause. For example, Mexicans lack of trust in the state is a result of corruption, not the other way around. And culture played no role in causing for the economies of North and South Korea have diverged.

Economics and the Ignorance Hypothesis

The ignorance hypothesis maintains that poor countries are poor because they have a lot of market failures. Rich countries are rich because they have figured out better economic policies. But as African nations have languished over the last half century under insecure property rights and economic institutions, impoverishing much of their populations, they did not allow this to happen because they thought it was good economics; they did so because they could get away with it and enrich themselves at the expense of the rest.

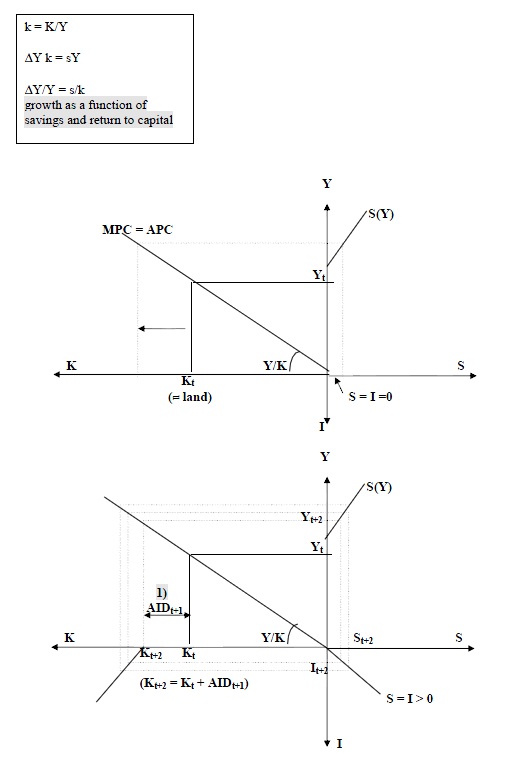

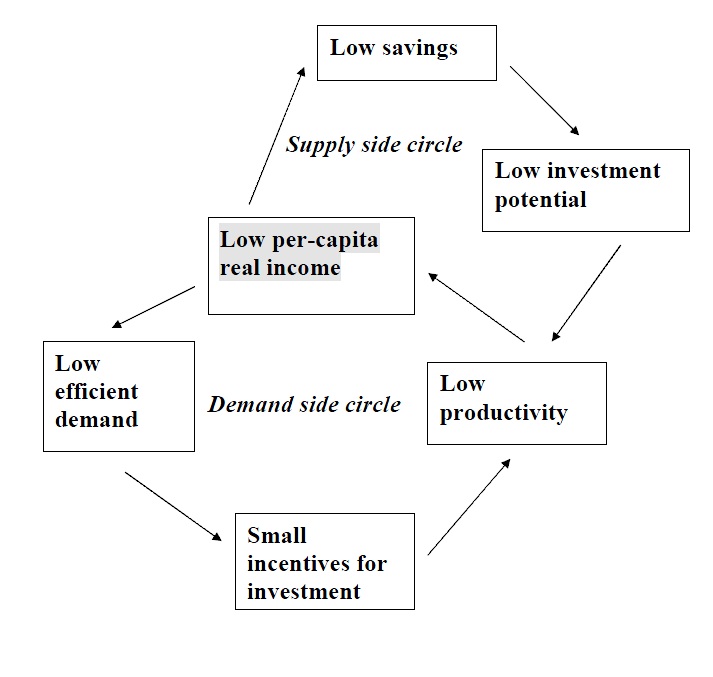

Diagrams to the right explain preconditions for lack of growth via a famous economic model from the 1950s called the “Big Push Model”. The model first introduced by Paul Rosenstein-Rodan in 1943 explains why poor countries are unable to transform themselves into rich countries. The reasoning is that the capital stock and hence income is too low to generate savings and investment. To break this vicious circle, the capital stock has to be increased. A “big push” in the form of aid would increase the capital stock (and break infrastructure bottlenecks), and raise the income to a level where net savings and domestic investments could take place. Increase savings/investment from below 5% (» depreciation) to above 10%, and subsequently higher. The vicious circle could be turned into a virtues circle.

Acemoglu and Robinson argue that for example, North Korea did not introduce private property, markets, private contracts, or working economic and political institutions. And North Korea continues to stagnate. South Korea in comparison, introduced economic institutions that encouraged investment and trade. South Korean politicians invested in education, achieving high rates of literacy and schooling. And South Korean companies were quick to take advantage of the relatively educated population. The policies encouraging investment and industrialization, exports, and the transfer of technology.

Acemoglu and Robinson’s Answer: Extractive and Inclusive Institutions

They outline two very different forms of institutions, the extractive and the inclusive. And these are at the heart of Acemoglu and Robinson’s model.

Extractive institutions extract from the many to the benefit of the few.

- Extractive economic institutions are designed to extract from the many to the benefit of the few (low wages, elite captures spoils, supported by extractive political institutions).

- Extractive political institutions are designed to extract power from the many to the benefit of the few (concentrate power in the hands of the few).

Inclusive institutions work in the opposite manner. Instead of extracting they seek to include people under their umbrella.

- Inclusive political institutions create an equal distribution of power (pluralism, opposite of absolutism)

- Inclusive economic institutions provide property rights, free trade, and a market economy. In which everyone can participate on a fair level playing field.

Nations with inclusive institutions have a set of rules in society that allow individuals to freely make decisions in the political and economic sphere. This can take the form of education, the ownership of assets and the right to have them protected, the opportunity to start enterprises and take on any occupation. Successful economic growth rests on being able to harness the talents, creativity, skills and ideas of its people.

Nations with extractive institutions create barriers for people to use their skills which only benefit a very small subset of society. Most poor countries don’t offer access to quality education. There are monopolies and barriers to entry when it comes to enterprise. Most people don’t have secure property or asset rights and there’s no equality before the law. This results in enormous amounts of wasted talent and wasted economic potential.

Acemoglu and Robinson’s answer is as compelling as it is fundamental. But there are also many other important aspects indeed also related to their institution model. As these can be seen among those countries with the most successful implemented versions of inclusive institutions, such as creative destruction.

Creative destruction

Creative destruction is a fundamental concept of capitalism. First introduces by Joseph Schumpeter, it describes the “process of industrial mutation that incessantly revolutionizes the economic structure from within, incessantly destroying the old one, incessantly creating a new one.” It is a central part of the economic theory of economic innovation and the business cycle.

Creative destruction is essential to sustained growth via innovation. Acemoglu and Robinson argue that extractive institutions counteract creative destruction. With elites dominating extractive institutions, and are unwilling to change the status Quo via any form of economic or technological innovation. But Acemoglu and Robinson’s institutions would explain why extractive institutions can generate some growth, but they will usually not generate sustained economic growth, and certainly not the type of growth that is accompanied by creative destruction.

Positive feedback

But inclusive economic and political institutions do not emerge by themselves. They are often the outcome of a significant conflict between elites resisting economic growth and political change and those wishing to limit the economic and political power of existing elites. Acemoglu and Robinson argue that inclusive institutions emerge during critical junctures, such as during the Glorious Revolution in England or the foundation of the Jamestown colony in North America, when a series of factors weaken the hold of the elites in power, making their opponents stronger, and creating incentives for the formation of a pluralistic society. The outcome of the political conflict is never certain though and even if in hindsight we see many historical events as inevitable, the path of history is contingent.

An example of a positive feedback is free media. As inclusive political institutions allow free media to flourish, free media often provides information about and mobilizes opposition to threats against inclusive institutions.

Vicious Circle

But as there are positive feedback effects, there are also those working in the opposite direction. The logic and negative fact behind that of vicious circles are that extractive political institutions give rise to extractive economic institutions, which in turn help elites to remain in power.

But the solution to the economic and political failure of nations today is to transform their extractive institutions toward inclusive ones. Although difficult it is not impossible, and the iron law of oligarchy is not inevitable. Nevertheless, once in place, inclusive economic and political institutions tend to create a virtuous circle, a process of positive feedback, making it more likely that these institutions will persist and even expand.

Why England?

There are many factors to why England was especially successful, and why England, in particular, gave rise to the industrial revolution. England is therefore also an especially interesting example of how successful aspects and preconditions merge into what would prove to be a prosperous outcome.

Pluralism and The Glorious Revolution

The glorious revolution was shaped by several interlinked processes with opponents of absolutism, to stop attempts to restore a new absolutist regime in England. It was indeed a very important aspect and a uniquely English event. It made the political system open and responsive to the economic needs of society (inclusive economic institutions, innovation, competition and creative destruction).

Pluralistic political institutions are especially important for inclusive political and economic institutions. And this was also a unique aspect of English history. As some in parliament fighting to remove James II in the wake of the Glorious Revolution imagined themselves playing the role of the new absolutist, such as Oliver Cromwell after the English Civil War. But the fact that Parliament was already powerful and made up of a broad coalition consisting of different economic interests and different points of view made the iron law of oligarchy less likely to apply in 1688.

With pluralism, no group wants or dares to overthrow another for fear that its own power would suffer at the same time, and the broad distribution of power makes such an overthrow difficult. A supreme court can have power if received broad enough support from the rest of society. The logic of the virtuous circle also meant that such repressive steps would be increasingly unfeasible, again because of the positive feedback between inclusive economic and political institutions. Inclusive economic institutions lead to a more equitable distribution of resources than extractive institutions. As such, they empower the citizens at large and thus create a more level playing field, even when it comes to the fight for power. This makes it more difficult for a small elite to crush the masses rather than to give in to their demands, or at least to some of them. The British inclusive institutions also contributed greatly to the emergence of the Industrial Revolution. Britain was highly urbanized and using repression against an urban, concentrated, and partially organized and empowered group of people would have been much harder than repressing a peasantry or dependent serfs.

Pluralism also enshrines the notion of the rule of law, the principle that laws should be applied equally to everybody — something that is naturally impossible under an absolutist monarchy. But the rule of law, in turn, implies that laws cannot simply be used by one group to encroach upon the rights of another. What’s more, the principle of the rule of law opens the door for greater participation in the political process and greater inclusively, as it powerfully introduces the idea that people should be equal not only before the law but also in the political system.

As inclusive political institutions, support and are supported by inclusive economic institutions. This creates another mechanism of the virtuous circle. Inclusive economic institutions remove the most egregious extractive economic relations, such as slavery and serfdom, reducing the importance of monopolies, and creating a dynamic economy, all of which reduces the economic benefits that one can secure, at least in the short run, by usurping political power. Because economic institutions had already become sufficiently inclusive in Britain by the eighteenth century, the elite had less to gain by clinging to power and, in fact, much to lose by using widespread repression against those demanding greater democracy. This facet of the virtuous circle made the gradual march of democracy in nineteenth-century Britain both less threatening to the elite and more likely to succeed. This contrasts with the situation in absolutist regimes such as the Austro-Hungarian or Russian empires, where economic institutions were still highly extractive and, in consequence, where calls for greater political inclusion later in the nineteenth century would be met by repression because the elite had too much to lose from sharing power. Eastern Europe was in comparison to western European much more confined by the Iron Law of oligarchy.

The British Navy

English historian Dan Snow contributes another unique English aspect to its development, namely the British Navy. The enormous British navy was essential to the Empire. It was also essential to the English society and its economic development. The first central bank, The Bank of England, was conceived as an idea to help expand and maintain a large English fleet of warships. After England’s crushing defeat by France in 1690, this became a catalyst for England’s rebuilding itself as a global power. With no public funds available to rebuild the fleet, the Bank of England was founded. Government bonds were to be incorporated. The lenders would give the government cash (bullion) and issue notes against the government bonds, which can be lent again. The public began buying bonds and thereby loaning the government money for it to invest in the navy. The government promised to repay the loans with interest. £1.2m was raised in 12 days; half of this was used to rebuild the navy. Snow argues, “More than half of the Bank’s first loan from the money collected went to the Navy, with the Government paying it back with a tax raised on commercial shipping, which it was hoped a strong Navy would protect.”. The increasingly powerful fleet of warships protected an increasing fleet of commercial ships, which brought wealth to England and income via taxes to the state, who re-payed the loans to the public, which invested more in government bonds (a virtues circle). This ‘financial revolution’ was followed by agricultural and industrial revolutions also fueled largely by the Navy’s demand for food, iron, copper, and textiles. As the country’s biggest employer, the Navy bought tons of agricultural produce from farmers who, in turn, competed for contracts and explored more intensive ways of growing crops.

Why North America?

The North American case of success is naturally highly linked to that of the English. But Niall Ferguson, Acemoglu, and Robinson complement each other in outlining the North American progress in comparison to its South American neighbors.

Ferguson’s especially contributes John Lock and property laws for the U.S success story. For the early British colonies, there was a link between political representations and property ownership. And then the creation of a parliament.

In South America instead, the newly independent states began their existence without a tradition of representative government, with a fondly unequal distribution of land, with racial cleavages that proximate to that of economic inequality, the result was revolution and counter-revolution, as the property less struggled for a few acres more, while the elites clung to their haciendas. Time and again, democratic experiments failed, because, at the first sign of that they might be expropriated, the wealthy turned to the military to return the status Quo by violence.

Acemoglu and Robinson outline a unique aspect of European settlement in North America compared to South America. North America was very sparsely settled with vast stretches of land and few people. There was an essential aspect of property rights. Compared to the prosperous and densely settled areas, where Europeans introduced (or maintained) extractive institutions to force the local population to work in mines and plantations. In contrast, in sparsely settled areas, Europeans created institutions that provide secure property rights to a broad cross-section of the society, encouraging commerce and industry. The spread of industrial technology required the participation of a broad cross-section of the society—the smallholders, the middle class, and the entrepreneurs. Societies with good institutions took advantage of the opportunity to industrialize.

This series is a brief summary of the story of civilization. With as many colorful and varied aspects of human experience. This story is the story of us.

______________________________

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55099/2638a982-b4de-4913-8a1c-1479df352bf3-560x416.webp)

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55099/2638a982-b4de-4913-8a1c-1479df352bf3-350x260.webp)