The pandemic has caused extensive economic disruption and the government’s response has pushed the United States federal budget further out of balance. The U.S. government like its counterparts all over the world is spending trillions of dollars in response to the COVID-19 crisis. The Federal Reserve (Fed) and central banks around the world are doing extensive monetary stimulus. The Fed has lowered the federal funds rate rate to zero and implemented another round of quantitative easing.

Governments’ response to the pandemic was something newer witnessed before – a simultaneous demand and supply shock. Supply contracted (curve shifted inwards) as factories were shut down and logistics were effectively hampered with employers confined to their homes. Then demand contracted (curve shifted inwards) also, as consumers were confined to our homes. A no ordinary recession. Demand is now set to explode due to extensive stimulus, shifting the demand curve outwards, but the supply curve (production and logistics) will remain where it is for some time.

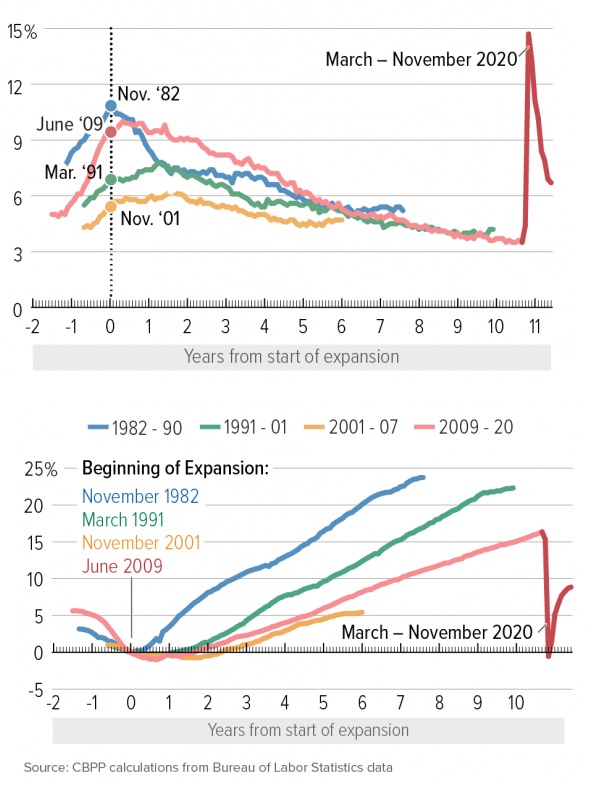

The rational for direct fiscal stimulus is to avoid companies going bankrupt, which would skyrocket unemployment and make it stickier. That in itself lowers demand and drags on the economic episode for a longer period of time.

All of this would seem deflationary, after all, we have largely lived in a disinflationary world for the past 40 years in terms of consumer prices. We have seen relatively low monetary inflation and a bull market in bonds with very low yields. It can be argued that have seen some form of asset price inflation, but not necessarily the Milton Friedman kind of monetary inflation pushing up the general price level, the consumer price index.

It is likely that this era is nearing an end, that monetary inflation could be making a comeback due to the very special circumstances that has occurred in connection with the Covid-19 pandemic, the response by governments, central banks and a shifting consumer beheavior.

The Case For Inflation

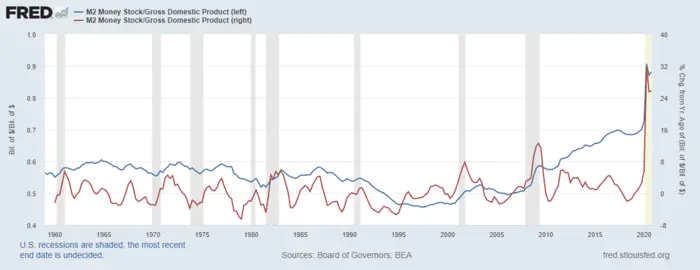

When it comes to the money supply and inflation, what really matters is the broad money supply (M2/ODL). We have seen unprecedented growth in the broad money supply since the onset of COVID-19. This extraordinary growth has become the means of explaining the swift rebound in asset prices.

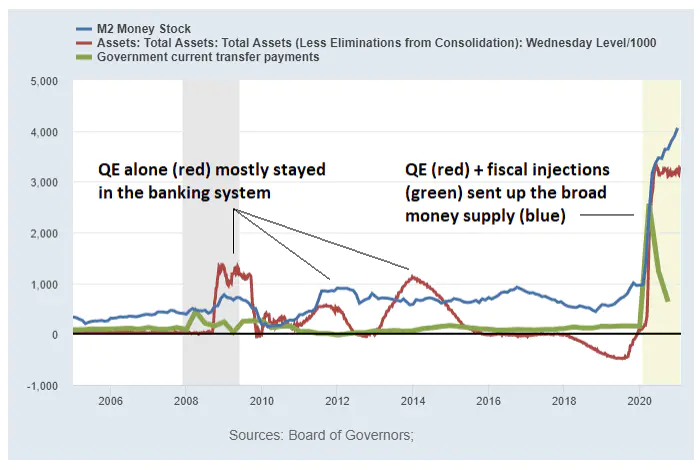

Money can be created in two ways; the traditional means via commercial bank lending or via direct monetization of newly issued federal debt. This distinction is crucial. Up until recently, it has been the commercial banks that have been able to claim sole responsibility for the growth in the broad money supply. The notion that quantitative easing (QE) conducted by itself is money creation is false. The Federal Reserve and other central banks have the ability to influence the base money supply (M0), but not the broad money supply.

Turning bullish on inflation this summer after 25 years of forecasting deflation in consumer prices, money manager and finance historian Russell Napier who do now believe that inflation is back. “The mechanism through which money is created has changed”, Napier said in an interview this week. calling the credit guarantees offered by governments to commercial banks making new loans “a revolution”.

Napier was among the few economists that stuck with his prediction of prolonged deflation in the face of QE1, QE2, QE3, and so on and so forth. While many financial analysts were worried about hyperinflation, let alone inflation, Napier said we’d see a lack of inflation. And he was right. To the anguish of those who kept on about money printing. Napier has now changed his mind, however, and is now anticipating a reversal and a breakout of inflation.

Why Didn’t Quantitative Easing Work?

Commercial banks create money via fractional reserve banking when lending occurs between said banks and consumers and businesses. QE is a means of capitalizing the banks, allowing them further scope to be able to lend against these freshly printed reserves with the central banks. QE is effectively just a swap of government bonds for central bank reserves; unless lent against the two are negligible. Getting banks to lend is what increases the broad money supply.

Napier argues that since commercial balance sheets wouldn’t expand, despite central banks’ balance sheets expanding. The interest rate policy that central banks pursued with QE created a huge boom in non-bank debt. QE was actually not creating growth in money but in debt, hence weakening the balance sheet and leading to disinflation/deflation, according to Napier.

QE for the last 10 years expanded central banks’ balance sheets and it gave a lot of reserves to the banks themselves, but the banks did not use these reserves as collateral to lend into the market. So lending, broad lending, didn’t take place. Money being lent by commercial banks is typically where most of the money supply comes from. That didn’t happen, so we had this deflationary environment where debt was growing but money was not.

Napier proposes a solution to make quantitative easing actually ‘work’ via what he calls re-intermediation of credit assets. This would entail governments or central banks to persuade commercial banks to buy back existing credit. The bank’s balance sheets would expand and they would have created money. This existing debt would comprise both government and private debt. Napier argues that this shouldn’t directly increase the level of debt, but the level of money – hence inflationary.

Fiscal + Monetary Stimulus = Inflation

If the central banks and governments work together, they are able to rapidly increase the base money supply and the broad money supply. This is what Napier and many others believe will be the impetus for a return of secular inflation; central bank-financed fiscal spending.

When a central bank is mandated to guarantee bank loans or does so on its own accord, or when a central bank is directly monetizing government deficits, then it is in the business of creating money.

We can see how this relationship has played out in the past. The chart below is the perfect illustration of how growth in the broad money supply over the past 15 or so years has not been a function of QE or government spending in isolation, but rather is a result of a combination of the two.

Are Low-Interest Rates Deflationary or Inflationary?

Low rates can actually be deflationary when they don’t create any more money, but instead debt. Monetary policy is about the quantity of money and not the price of money. The price of money is a technique to adjust the quantity of money.

Napier explains that the low-interest rates in the western world that have persisted for a decade have instead led to deflationary pressure instead of inflationary since the price of money adjusted the quantity of debt without adjusting the quantity of money.

Central banks are only allowed to lend, they aren’t allowed to print (at least not yet). The fact that we have these low rates, that have caused a buildup of debt, and the only way central banks can fix that is to add even more to the debt – it’s a deflationary spiral.

Get Ready for the Return of Inflation

The government guarantee programs for commercial banks’ debt in response to the Covid-19 pandemic and the coordination of loose fiscal and monetary policy is why inflation is likely to return with a vengeance.

The government guarantee programs for commercial banks’ debt is manipulation of the banking system does, and in essence, imply that governments control monetary policy (also referred to as “Fiscal Dominance”). This change is permanent and not temporary.

Governments across the world decided that the best way to keep people and businesses alive during Covid-19 was to get credit flowing through the banking system “to people who needed it”. They did it via the existing financial system down to specific bank accounts of people and businesses. This was done in the U.S. via the so-called Small Business Administration and the banking system.

The U.K. government made £ 40 billion GBP available via the so-called Coronavirus Bounce Back Loan program. The UK banking system has been very bad at lending during the past 10 years, but that has now changed according to Napier. The banks now suddenly found 40 billion credits to lend since these aren’t commercial credits, they are government credits. The government has guaranteed the principal on those loans.

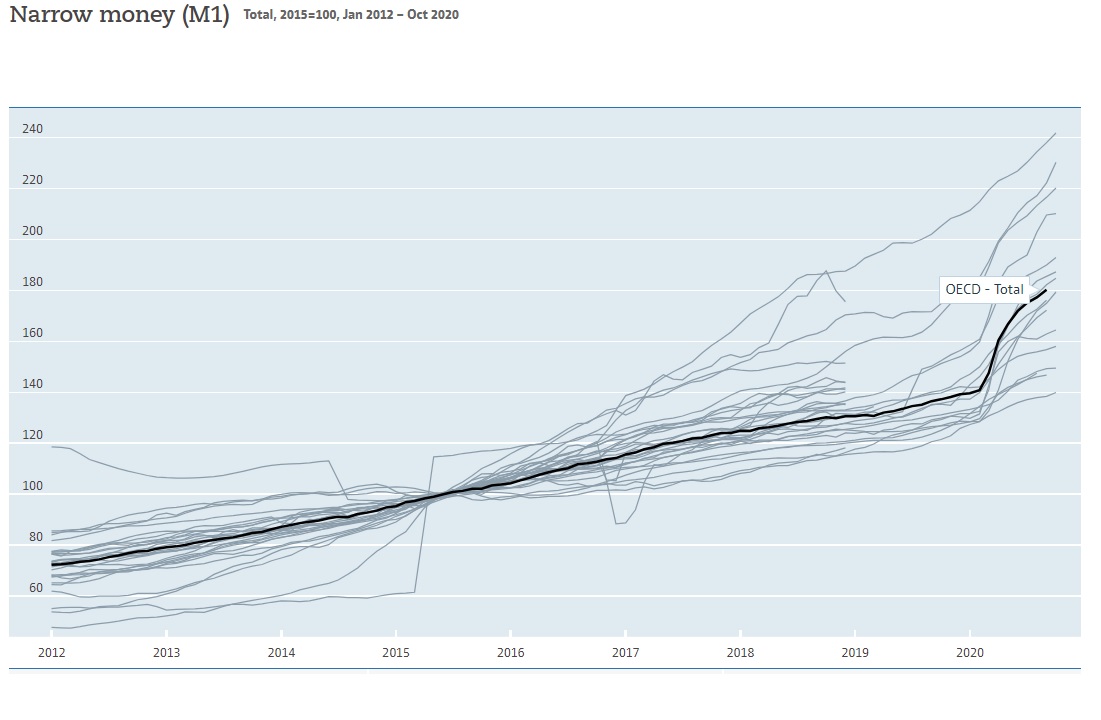

So, commercial banks whose balance sheets had been going flat line for the last 10 years suddenly went vertical, it went ballistic. With the government guaranteeing the credit risk, everything changed. They have created money. The stunning statistic of all of this is the end result affecting the inflation rate.

The OECD total money supply growth number. In the deepest recession since World War II, we’ve got the fastest money growth in money since 1981. There isn’t necessarily a link between the scale of growth of money and inflation. But the transformational thing is already behind us, we have gone from broad money growth of about 6 to 7 % previously to 17,5 % globally in 6 months. Inflation expectations will jump.

Consumer Behavior

The velocity of money is important for measuring the rate at which money in circulation is being used for purchasing goods and services. The velocity of money is the gauge for how the broad money supply will impact consumer prices. Put simply, it is the rate at which money is exchanged in an economy through transactions between lenders and borrowers, buyers and sellers. Whilst the relationship between money velocity and CPI is clear, unfortunately, M2 money velocity still remains near its lowest point in over 60 years.

With the economy returning to some normality post-Covid-19, the velocity of money will increase and the result of what has been explained above will be reflected in the inflation rate that should increase. The inflation genie is then out of the bottle and it won’t be easy to put it back in.

As the restrictions subside consumers and businesses will finally spend and release a wave of pent-up demand that ought to provide a reflationary tailwind to CPI.

If inflation takes off, this might in turn affect consumer behavior by shifting consumption patterns to the near term instead of the long term. If prices are anticipated to rise in the future, moving consumption to the near term makes sense. This makes even more sense for consumer goods that aren’t degradable.

If consumption patterns hence shift to increasingly buy consumer goods to the near term instead, this will, in turn, raise the velocity of money, it will increase the inflationary pressure, and hence, in turn, drive up prices.

Fiscal Dominance & Political Instability

History suggests that paradigm shifts are quite often reinforced by political shifts and we are now entering an era of central bank-financed fiscal spending. It seems likely that the U.S. Congress will no longer be as constrained in their spending efforts to what they can do, but rather what they are politically obliged to do.

Fiscal dominance and MMT are easily justified by politicians. Central bankers have tried endlessly to get inflation; it is a palatable solution to the wealth divide. Direct payments to individuals are the easiest and most assured way to get the money into the hands of individuals who actually have a higher marginal propensity to consume. QE alone does not and has not done this.

Another political change also has broad implications on what has been a major cause of deflationary pressure for the last 40 years – globalism and the rise of China. Globalization has seen the U.S. forfeit its entire manufacturing sector, favoring capital at the expense of labor. De-globalization, protectionism, tariffs, and trade barriers would go a long way to reverse this trend.

Protectionism would transfer power back to the younger workers and spenders, forcing companies to raise wages and thus provide a strong tailwind for a rise in consumer price inflation.

Another aspect to consider is the U.S. trade imbalance. We have recently seen China begun exporting inflation rather than the opposite. China’s producer prices – which measure what is sometimes called “inflation at the factory” – are rising.

Commodities trade at higher prices (we’ll get back to that) and a general ongoing price pressure at Chinese factories due to wage increases. These parameters will raise input costs and hence output costs as well. Since the US runs one of the world’s largest trade deficits relative to its economy it will increasingly import these higher prices.

Globalization reversal

It is clear that globalization is acting synergistically with deregulation, to put downward pressure on real prices. It has an effect that increases economic competitiveness and the political economy process that governs long-term inflation trends.

Reverse globalization appears to be a trend nowadays, however, we have the Brexit referendum, Trump’s election to the US president, trade protection, border crossing, and immigration control. Regardless of international responsibility, the trend around the world – even with the new administration in the U.S. – is to return to nationalism.

Are the Government Programs Here to Stay?

Bank credit is up from last year and it has expanded. But the question is if the type of programs launched in response to Covid-19 will last. Most of what we now see on the money supply is the result of what was done in and around May 2020 but the programs have since been winding down.

There is something on the launchpad in the U.S. called Main Street Lending Program, which is a $ 600 billion lending program. The programs so far have effectively been life-support. They are intended to keep businesses alive. The next program, the coming programs, will be recovery programs. And possibly after that, we will get green lending programs intended to spur on the development of environmental technology and the transformation of industries from using fossil fuels to ‘green’ energy.

Perhaps even social justice programs, there is an ongoing discussion in the U.S. concerning a program to pay reparations to descendants of slaves, a program that could come with a $12 trillion price tag. A coronavirus relief package froze student loan payments and interest until January 31. Americans hold over $1.7 trillion in student debt and the federal reserve estimates that 31% of all U.S. adults have student loans. Now, House Democrats have proposed “broadly” forgiving up to $50,000 of federal debt for student borrowers.

Commodities

Commodity prices have skyrocketed during the Covid 19 lockdowns. The lockdown has driven supply restrictions that have contributed to the rapid rise in many commodities.

It looks as if the trend will continue in 2021 with futures for lean hogs, corn, crude oil, gasoline, and lumber trading every higher. If we are to enter a period of continued commodity scarcity and thus a commodity bull market, this would no doubt provide an inflationary tailwind going forward.

Some believe that we are entering a commodity supercycle, a period when prices are well above their long-term trend. On the demand side, expectations of a recovery driven by global fiscal stimulus and successful vaccine rollout in developed world economies have boosted prices in the first three months of the year.

The Biden Administration’s proposed infrastructure package set to contribute to the increased demand for more industrial commodities, as well as the shift to a green economy. The Biden administration’s green investment program pledges $400bn on clean energy over the next ten years and Europe is committing to a greener world. Meanwhile, China’s January car sales are up 30% year-on-year and China’s copper consumption accounts for around half of the world’s production.

What will Central Banks Do?

If inflation breaks out, central bankers will be a few steps behind the curve as they busily reverse QE instead of hiking the cost of borrowing. They’ll be removed from control of the banking system – where the money supply is truly controlled.

The return of inflation would mark a huge turning point. We have been used to very low inflation – so much so that even 2 to 3 percent might make a huge difference to how we invest and feel, particularly if interest rates on savings don’t rise to compensate us (they won’t).

With the debt level being what it is today, very high, the central banks are in a tight spot. They can continue on with low-interest rates and expansionary monetary and fiscal policy – thereby continue to grow the already enormous debt. Or, they can increase interest rates to fight the (possible) inflation and thereby see an enormous wave of insolvency wash over the whole global financial fabric. They are i.e. damned if they do, damned if they don’t.

Rising rates as a result of inflation would mean the government would either need to issue more debt to finance its existing discretionary spending in the form of social security, defense, Medicare, and cover its increased interest costs. Or, correspondingly reduce spending in these areas.

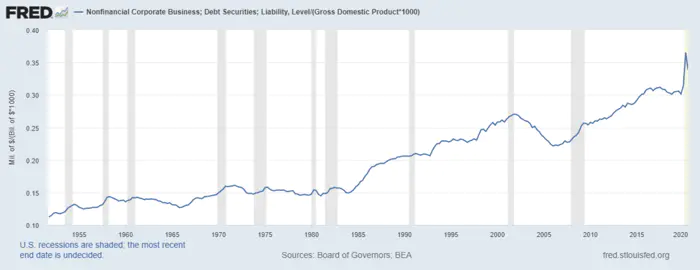

There is no political impetus to be able to cease its discretionary spending, but rather expand this spending, anything other than negative real rates is therefore unlikely to be sustainable. Rising rates are equally as impactful on the private sector too. Corporate debt as a percentage of GDP remains at all-time highs.

The yield curve will steepen in response to inflation, whether the central banks want it or not. If we do get inflation and we see central bankers that do not allow bond markets to function property and price this inflation, then they will at some point need to step in with some form of yield curve control. Yield curve control works to remove the market’s ability to price long-term yields.

Or they might just let inflation run hot (especially if it’s believed to be just transitory and temporary). The Federal Reserve has recently made a subtle but significant change in their inflationary mandate; as opposed to aiming for their traditional target of 2% annual inflation, they will instead now attempt to create average inflation of 2% annually. Average inflation targeting affords the Fed the ability to overstimulate the economy.

If inflation is rising without a subsequent rise in interest rates, then the purchasing power of debt will be inflated away without an increase in the purchasing power of consumers. That might just be what central bankers and governments all around the world want. If inflation is allowed to run hot, whilst the government is allowed to continually finance its deficits at capped negative real yields, then this allows governments (specifically the U.S.) to essentially inflate away its debt.

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55124/79bc18fa-f616-4951-856f-cc724ad5d497-560x416.webp)

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55099/2638a982-b4de-4913-8a1c-1479df352bf3-560x416.webp)

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55136/b1b0b614-5b72-486c-901d-ff244549d67a-350x260.webp)

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55124/79bc18fa-f616-4951-856f-cc724ad5d497-350x260.webp)

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55099/2638a982-b4de-4913-8a1c-1479df352bf3-350x260.webp)