A team of British researchers has devised a new method that they believe has “tremendous potential” in treating all types of cancer.

The researchers have manipulated the body’s own defense against tumors with gene editing using the so-called Crispr-Cas9, and in this way managed to teach T-cells to attack most cancers leaving healthy cells unharmed.

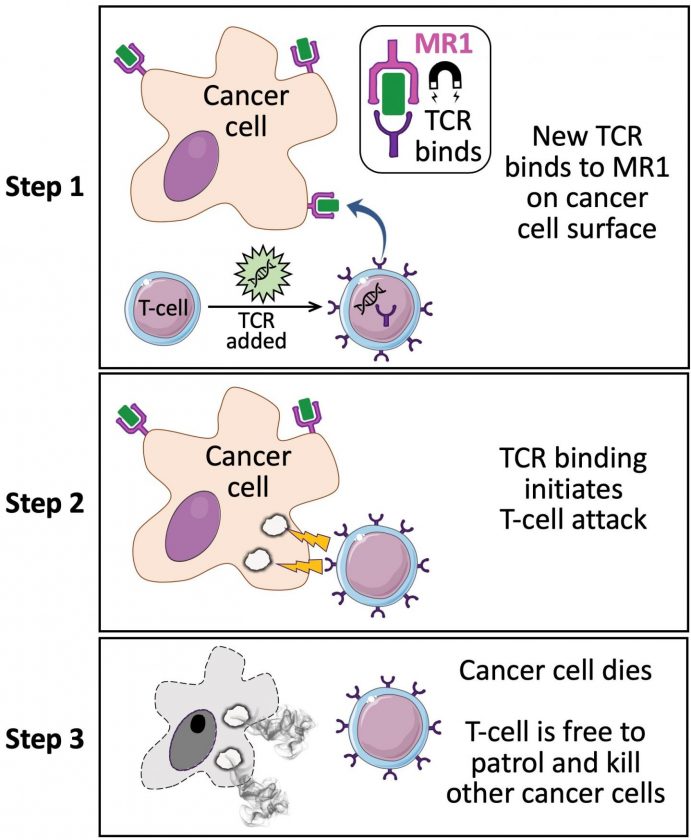

T-cells (lymphocytus T) use a receptor protein called a T cell receptor (TCR), which essentially “looks” at the proteins being produced by a cell and if those proteins are abnormal — e.g. if the cell is cancerous or infected with a virus — the T-cell can become activated to kill the abnormal cell.

Improving the efficacy of this process is the goal of many cancer immunotherapies. A drawback is a reliance on a group of protein molecules called ‘major histocompatability complex’ (MHC), whose sequence varies greatly from person to person. MHC is required in the process of T-cell activation.

The new discovery, which comes from scientists based at Cardiff University, researchers have identified a kind of T-cell with a novel TCR that doesn’t act through MHC, but through a different protein called MR1 (major histocompatibility complex class I-related gene protein).

Unlike MHC, MR1 does not vary in the human population and is thus a hugely attractive new target for immunotherapies.

“Cancer-targeting via MR1-restricted T cells is an exciting new frontier—it raises the prospect of a ‘one size fits all’ cancer treatment, a single type of T cell that could destroy many different types of cancers across the population.”

– Cardiff’s Andrew Sewell, Ph.D., a professor of infection and immunity.

T cells equipped with the new TCR (MR1) were shown, in the lab, to kill lung, skin, blood, colon, breast, bone, prostate, ovarian, kidney, and cervical cancer cells, while ignoring healthy cells. To test the therapeutic potential of these cells in vivo, the researchers injected T cells able to recognize MR1 into mice bearing human cancer and with a human immune system.

“An MR1-restricted T cell clone mediated in vivo regression of leukemia and conferred enhanced survival of NSG mice,”

“TCR transfer to T cells of patients enabled killing of autologous and nonautologous melanoma. These findings offer opportunities for HLA-independent, pan-cancer, pan-population immunotherapies.”

– The article’s authors wrote.

The Cardiff group hopes to trial this new approach in patients toward the end of this year following further safety testing. The study, “Genome-wide CRISPR–Cas9 screening reveals ubiquitous T cell cancer-targeting via the monomorphic MHC class I-related protein MR1,” was published in Nature Immunology.

Reference:

Michael D. Crowther et al Genome-wide CRISPR–Cas9 screening reveals ubiquitous Tcell cancer targeting via the monomorphic MHC class I-related protein MR1 | VOL 21 | FEBRUARY 2020 | 178–185 | DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41590-019-0578-8

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55136/b1b0b614-5b72-486c-901d-ff244549d67a-350x260.webp)

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55124/79bc18fa-f616-4951-856f-cc724ad5d497-350x260.webp)

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55099/2638a982-b4de-4913-8a1c-1479df352bf3-350x260.webp)