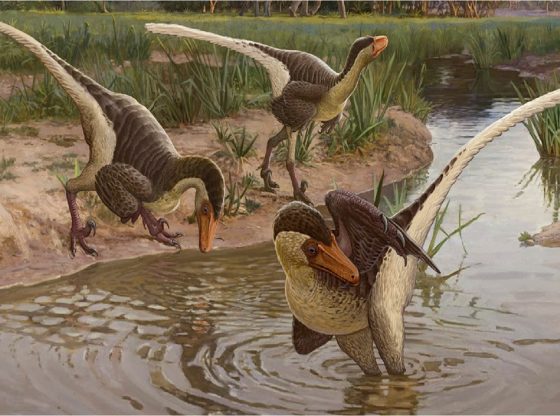

About 66 million years ago, an asteroid smashed into Earth, triggering a mass extinction that ended the reign of the dinosaurs and snuffed out 75 percent of life. Although the asteroid killed off species, new research led by The University of Texas at Austin has found that the crater it left behind was home to sea life less than a decade after impact, and it contained a thriving ecosystem within 30,000 years—a much quicker recovery than other sites around the globe.

“Life finds a way,” said Dr. Ian Malcolm, played by Jeff Goldblum, in the 1993 movie Jurassic Park. Life certainly does, as exemplified by the findings of a new study on the crater left behind by the asteroid that killed the dinosaurs.

The asteroid triggered a mass extinction, killing off 76 percent of life on Earth. But the scientists were surprised by the new findings, which undermine a theory that recovery at sites closest to the crater was slower because of environmental contaminants released by the impact, such as toxic metals.

The evidence suggests instead that recovery around the globe was influenced by local factors, which could have implications for environments altered by climate change today.

“We found life in the crater within a few years of impact, which is really fast, surprisingly fast,”

“It shows that there’s not a lot of predictability of recovery in general.”

– Chris Lowery, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics who led the study, said in a press release.

The research shows that once the initial dust settled, the survivors almost instantly spread into new environments to take advantage of changed conditions and a lack of competition.

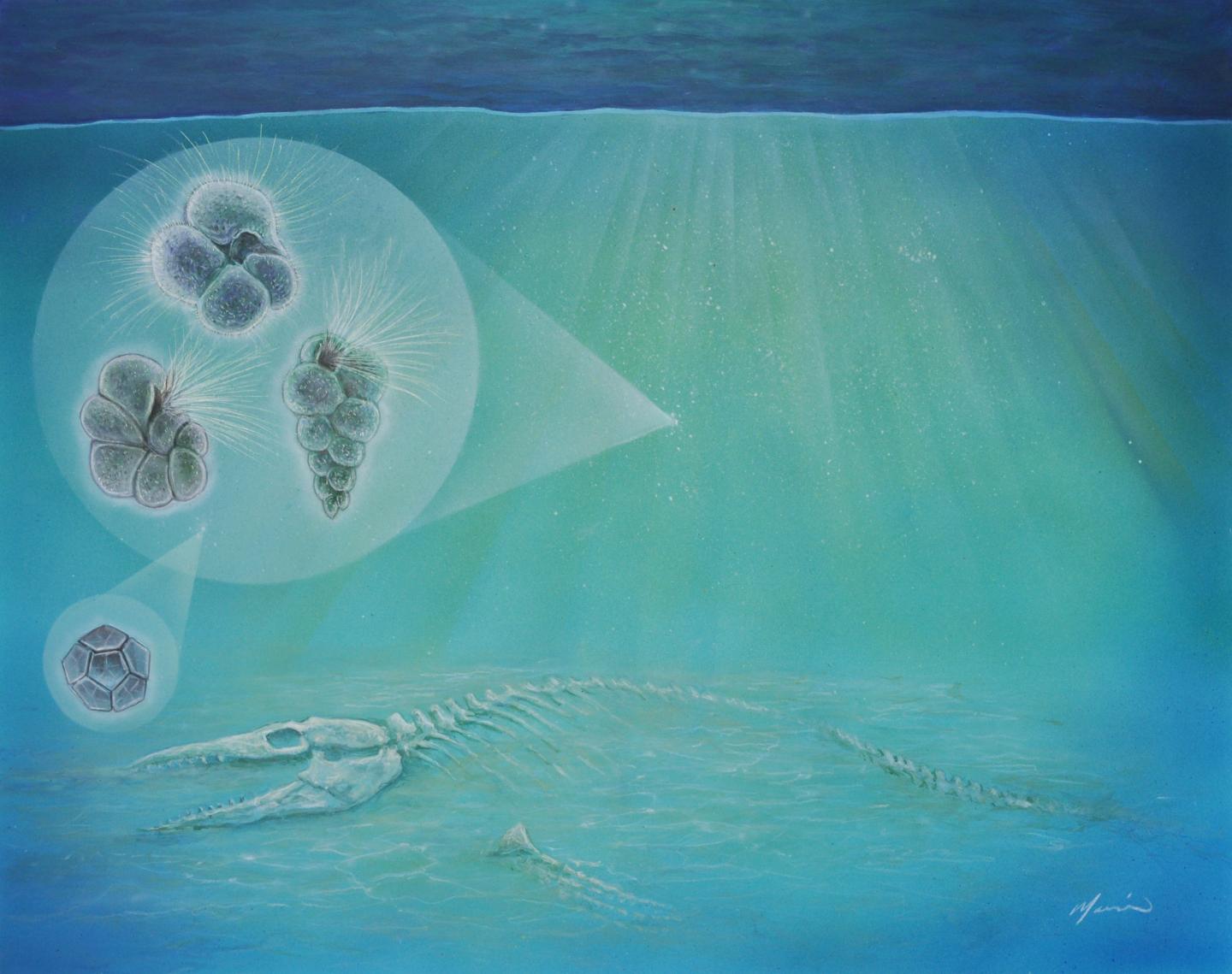

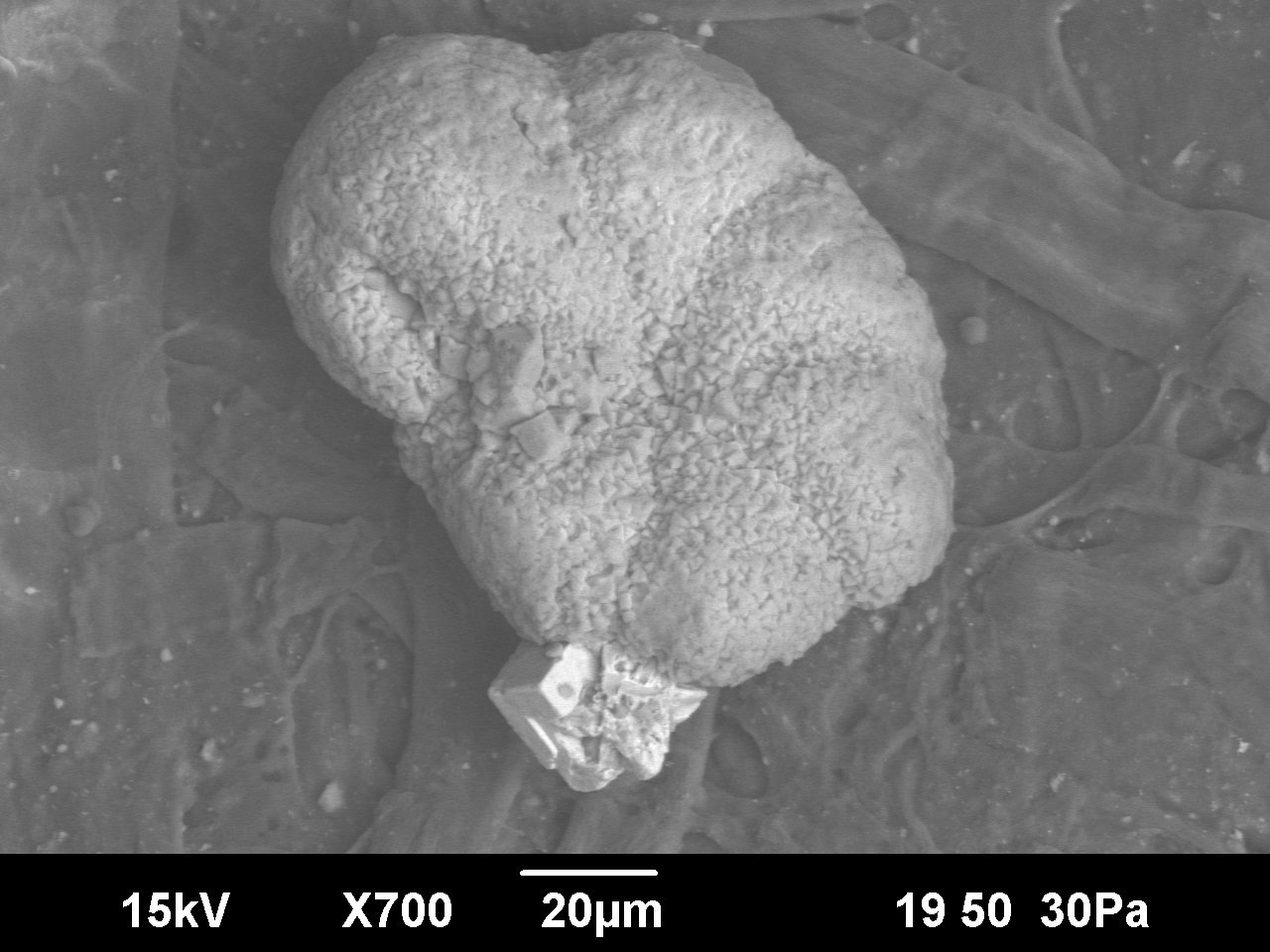

The evidence for life comes primarily in the form of microfossils—the remains of unicellular organisms such as algae and plankton—as well as the burrows of larger organisms discovered in a rock extracted from the crater during recent scientific drilling, conducted jointly by the International Ocean Discovery Program and International Continental Drilling Program.

The tiny fossils are hard evidence that organisms inhabited the crater, but also a general indicator about habitability in the environment years after impact. The swift recovery suggests that other life forms aside from the microscopic were living in the crater shortly after impact.

The researchers found the first evidence for life, including burrows made by small shrimp or worms, just two to three years after the extinction-level event. By 30,000 years later, blooming phytoplankton plants were supporting a diverse ecosystem of creatures large and small in surface waters and on the seafloor. On the other side of the world, there were areas that took up to 300,000 years to recover to that level.

The research was published May 30 in the journal Nature. UTIG research scientists Gail Christeson and Sean Gulick and postdoctoral researcher Cornelia Rasmussen are co-authors on the paper, along with a team of international scientists. UTIG is a research unit of the Jackson School of Geosciences.

Reference:

Christopher M. Lowery et al. Rapid recovery of life at ground zero of the end-Cretaceous mass extinction, Nature (2018). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-018-0163-6

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55136/b1b0b614-5b72-486c-901d-ff244549d67a-350x260.webp)

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55124/79bc18fa-f616-4951-856f-cc724ad5d497-350x260.webp)

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55099/2638a982-b4de-4913-8a1c-1479df352bf3-350x260.webp)