With the help of the CrisprCas9, researchers have managed to prevent deafness in mice who had otherwise developed severe hearing damage later in life. The result gives hope for new treatment methods for people with genetic hearing impairment.

These mice had a mutated gene that causes them to lose their hearing over time, just like in humans. Mutations in the TMC1 gene account for between four and eight percent of all cases of genetic deafness in humans. The gene encodes a protein that is crucial for hearing, it helps to convert sounds into electrical signals that can be transported to the brain.

Nearly half of all cases of deafness have a genetic root, but current treatment options are limited. However, the advent of new high-precision gene editing tools such as Crispr has raised the prospect of a new class of therapies that target the underlying problem.

Those that have the mutation will gradually lose their ability to hear, a process that often begins during childhood and then after 10 to 15 years, the hearing has been completely lost.

The researchers used CrisprCas9 technology on live newborn mice carrying a mutated TMC1 gene. Then, with the help of crispr/cas9, the researchers were able to cut into the genome and turn off the mutated gene.

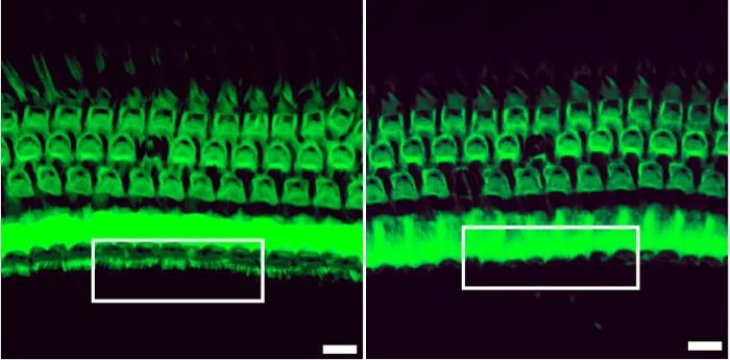

Eight weeks after the mice were treated, the researchers tested their hearing through noises. The mice that were treated responded to the sounds while the mice that were not treated but who had the mutation did not.

Other measurements showed that the mice treated had almost the same number of hair cells left in the inner ear as healthy mice, indicating that they heard about the same.

The researchers argue that the treatment is a safe and effective method to treat an animal that has a genetic mutation. They now hope that the research will contribute to the development of treatments for genetic hearing impairment in humans.

“We hope that the work will one day inform the development of a cure for certain forms of genetic deafness in people.”

– Prof David Liu, who led the work at Harvard University and MIT.

The study has been published in Nature.

Reference:

Xue Gao, Yong Tao et al. Treatment of autosomal dominant hearing loss by in vivo delivery of genome editing agents doi:10.1038/nature25164

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55136/b1b0b614-5b72-486c-901d-ff244549d67a-350x260.webp)

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55124/79bc18fa-f616-4951-856f-cc724ad5d497-350x260.webp)

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55099/2638a982-b4de-4913-8a1c-1479df352bf3-350x260.webp)