Adam of Bremen’s depictions of the Norse cultic center ‘Gamla Uppsala’ is an important historical account. A significant source of knowledge about ancient Scandinavian religious practice and sacrificial rituals. But as a cleric, his association is also problematic from a historical source-critical point of view.

Adam of Bremen was a German medieval chronicler. Little is known about him but he was probably born before 1050 CE and we know that he died on the 12 October of an unknown year (possibly 1081, at the latest 1085). His missionary activity for the church of Bremen, in what is now Germany, allowed him to gather information on the history and the geography of Northern Germany and Scandinavia.

His stay at the court of Svend Estridson, king of Denmark, provided him with the opportunity to gather information about the history and geography of the other Scandinavian countries at the time of the Viking Age (generally defined 793 to 1066 CE) and the Old Norse religion. The old Norse religion developed from early Germanic religion, that probably spanned over all of ancient Europe pre-Roman empire and was first described by Roman historian Tacitus’s Germania, in the 1st century CE.

Adam of Bremen’s chronicle describes the period during which the pagan traditions of Scandinavia were coming to an end, the Christian Catholic church would just within a couple of decades have total hegemony in northern Europe.

Adam of Bremen’s depiction of ‘Gamla Uppsala’ (Swedish “Old Uppsala”) in the book ‘Gesta Hammaburgensis Ecclesiae Pontificum’ is recognized as an important source of Norse pagan cultural traditions. The book was written in the 1070s CE and is a chronicle of the Archbishop’s seat in Hamburg-Bremen.

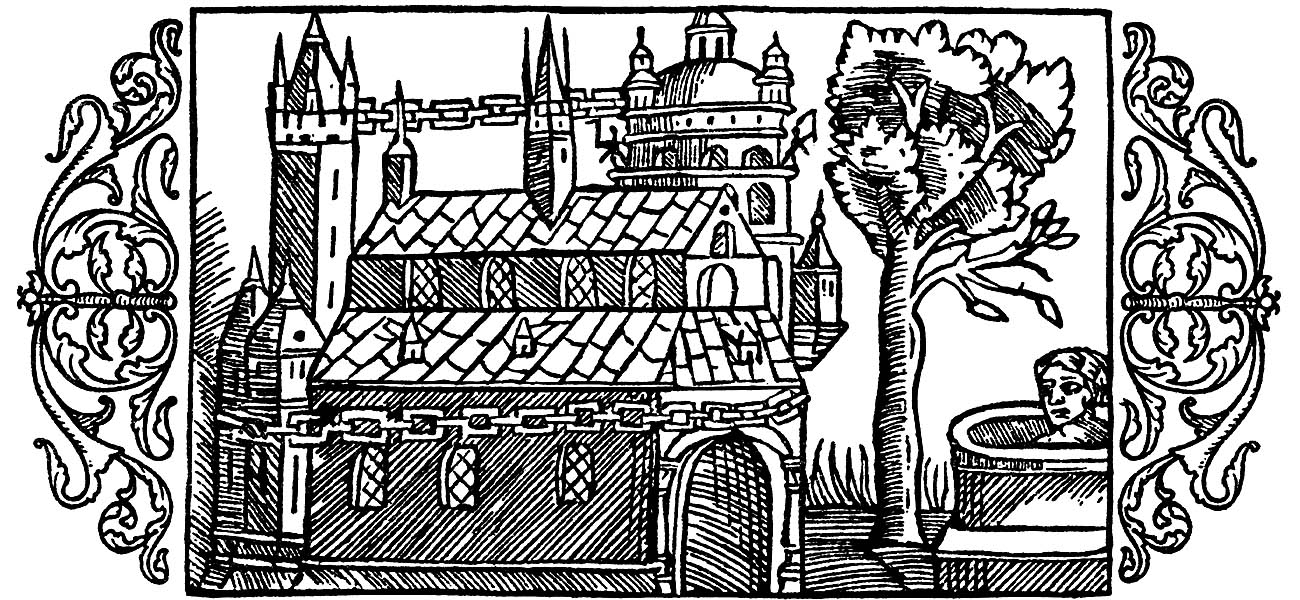

The Temple at Uppsala

In one of the chronicles, Adam describes a temple located near a city called Sigtuna. He describes how the temple is adorned with gold and with three depicted gods; Tor in the middle, which Adam calls “the most powerful”, Oden and Freyr on his side.

Oden armed, like Thor with a scepter and Freyr with a visible fallos, not surprising considering Freyr was a fertility god in Norse mythology. Adam compares Oden to Mars and Thor to Jupiter of ancient Greek mythology. Which is interesting considering other sources of Norse mythology often describes Oden as highest of the god, more similar to Jupiter.

Adam further describes how the temple is surrounded by hills as an amphitheater and that sacrificial festivities are regularly staged at this very important place in Viking Age Scandinavia. He also describes how an immense tree stands adjacent to the temple. This tree has far-spreading branches and is evergreen both in summer and winter.

Near that temple is a very large tree with widespread branches which are always green both in winter and summer. What kind of tree it is nobody knows. There is also a spring there where the pagan are accustomed to perform sacrifices and to immerse a human being alive. As long as his body is not found, the request of the people will be fulfilled.

He describes a spring where sacrifices are held. According to Adam, there is a custom where a man is thrown alive into the spring, and if he fails to return to the surface, “the wish of the people will be fulfilled.”

Adam describes the sacrificial customs that relate to ‘bithja’ (a family relationship to the English “bid” and is usually translated as “ask”) and ‘blóta’, to sacrifice for blessings of the people in dedication, appeasement, to the gods.

One of the more important traditions of old Norse practices is the ‘Midvinterblot’ (roughly translated mid-winter-sacrifice). It was an annual feast probably held at the winter solstice in December and it may have coincided with the Germanic pagan festivity, and it is therefore called in some more recent sources, jólablót/julblot (Christmas).

According to the Norse sagas describing the Midvinterblot, the people sacrificed livestock to gain the gratitude and blessing of the gods for the coming year and the growing of crops. The main sacrificial animals, whose meat was boiled and eaten by the blot, were of horses, pork, beef, and sheep. They devoted themselves to sumptuous amounts of beer and mead, in honor of the gods.

Offerings to the gods depend on the situation given, for example, when confronted by famine, sacrificial offerings are made in Thor’s honor, in times of war in Oden’s honor, and in marriage, in Freyr’s honor. Adam also mentions that there are annual celebrations by which those who have converted to Christianity must buy themselves free from the ceremonies.

He further describes in detail how nine males of “every living creature” are offered up for sacrifice, and tradition dictates that their blood placates the gods. They are hanged in trees as sacrificial offerings to the gods. Adam reports that a Christian man informed him how he saw 72 bodies of different species hanging in the sacrificial grove.

The sacrifice is as follows; of every kind of male creature, nine victims are offered. By the blood of these creatures, it is the custom to appease the gods. Their bodies, moreover, are hanged in a grove which is adjacent to the temple. This grove is so sacred to the people that the separate trees in it are believed to be holy because of the death or putrefaction of the sacrificial victims. There even dogs and horses hang beside human beings.

This grove is found beside the temple and is considered extremely sacred to the heathens, so much so that each singular tree “is considered to be divine,” due to the death of those sacrificed or their rotting corpses hanging there, and that dogs and horses hang within the grove among the corpses of men.

Adam expresses disgust for the music and songs that are sung in conjunction with the procession, that they are so disgusting that they are best transferred to silence.

Source Criticism

The descriptions by Adam is not unproblematic from a source-critical perspective. The book was written around 1070 CE, that is, relatively close to the time when the events took place. Which in itself, under normal circumstances, should strengthen the reliability of the source, but here problems arise in this context regarding the objectivity of its author.

Adam was not present at the time when the ritual he describes took place, instead, he reiterates what is supposed to be the observations of other people as eyewitnesses. This, of course, makes a source less reliable regardless of context, even less in this context, when we return to the lens, for the eyewitnesses.

One should ask the questions; to whom was the chronicle intended? And for what purpose? This is essential as it means that the entire description and analysis must be based on this. Adam wrote the chronicle for the Catholic Church and was intended to be read by clerics in Rome. Therefore, dilemmas concerning the descriptions are given. That Adam is colored by the fact that describing the non-Christian heathens of the north to appear in poor light, and therefore of missionary priority of the Catholic Church, is particularly important.

In addition, according to Adam’s own statement, the description is partially witnessed and rendered by a Christian man – how true is this man’s reproduction of events?

That the chronicle, therefore, is written at the time the cult existed, does not make the description more reliable, rather the opposite. Professor Anders Hultgård at Uppsala University has presented a source-critical analysis that came to the conclusion described in the book by Gro Steinsland’s ‘Fornnordic Religion’.

“The ritual feast, the sacrifice, the gods, the sites linked to the trees and the source are all elements that may have belonged to pagan cult practices.”

Professor Hultgård also argues that human sacrifice in Scandinavia during the time of Christianity gradually replacing paganism, is not unbelievable, but hardly a part of public festivities.

There are examples of human sacrifice from the Viking Age when a woman in Norway was sacrificed and buried with a queen in the 830s, Ibn Fadlan’s descriptions of sacrifice in connection with the death of a chieftain in what is now Russia.

Human sacrifice seems to have been a cultural practice more common before the Iron Age of Scandinavia, as indicated by findings of so-called bog bodies all over Europe, these are human cadavers that have been naturally mummified in a peat bog, they are geographically and chronologically widespread, having been dated from between 8,000 BCE.

Archeological Findings

The archeological findings at Gamla Uppsala are extensive. It appears as if people have been buried at the site for at least 2,000 years. The site is believed to have been marked by between 2,000 and 3,000 burial mounds, most of which have now become farmland, gardens, and quarries. Today only 250 mounds remain. Among these are the great grave fields and the Royal Mounds, dated to the Roman Iron Age and the Germanic Iron Age. The Royal Mounds are the largest and are probably from the Scandinavian Vendel period (550 to 800 CE), pre-Viking Age.

Archeologists have found the remains of one or several large wooden buildings under the present church in Gamla Uppsala and some archaeologists believe that these are the remains of the famous pagan Temple of Uppsala, while others hold that comes from an earlier Christian wooden church. It is a common practice throughout Scandinavia to build Christian churches on top of pre-Christian sacred sites, as a symbolic manifestation of replacing one religious practice with another.

Using ground-penetrating radar and other geophysical methods, some startling findings were made in 2013. The remains of two lines of large wooden poles were discovered. One line is approximately one kilometer (0.62 miles) in length consisting of 144 poles and the other half a kilometer with each pole being separated by 5–6 meters.

The shorter line is perpendicular to the first, located a kilometer to the south and broken into a corner, which indicates that if the lines mark an enclosure similar to what is found at Jelling Denmark. This enclosed area would be by far the biggest structure north of the alps at this time in history.

Recent excavations in 2012 revealed several previously unknown buildings, one large building dated to the Germanic Iron Age, and some thirty so-called ‘grophus’, smaller buildings dated to between 550 and 1050 CE. Similar numbers of grophus have been found at ancient power centers in Denmark and Germany, which strengthens the theory of Gamla Uppsala as an ancient power center in Scandinavia.

References:

Sawyer and Sawyer, “Medieval Scandinavia: From conversion to reformation circa 800-1500”, 2010, University of Minnesota Press

Adam av Bremen, Anders Hultgård, översättning, ”Uppsala och Adam av Bremen”, 1997, Nya Doxa Lebedynsky, I.. (2006). Les Indo-Européens, éditions Errance, Paris

Remy, Arthur F.J. “Adam of Bremen.” The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907. 20 Sept. 2012

Archeology Museum: Monument discovered at Old Uppsala

Uppsala unearths pagan road of old kings