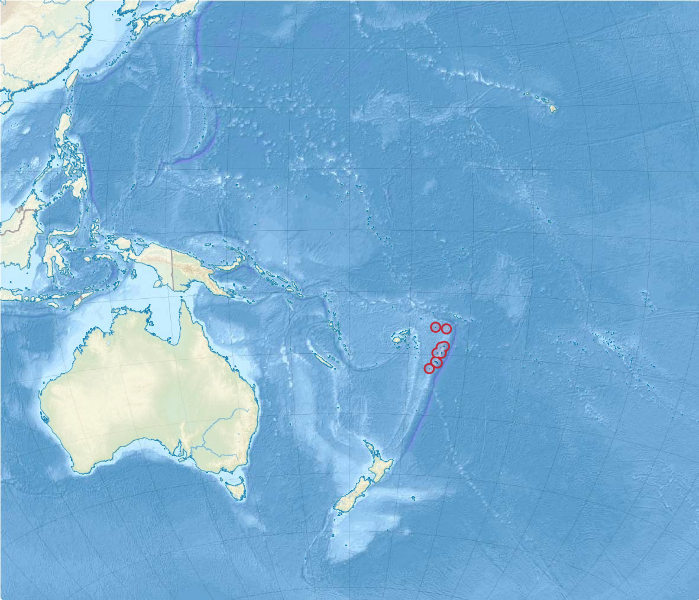

Some 3,000-year-old DNA provides new clues to how the islands far out at sea in the eastern Pacific was first populated.

An international research team has analyzed DNA from archaeological findings from four ancient individuals who once lived on the islands of Tonga and Vanuatu.

The first people arrived on these islands around three thousand years ago. But contrary to previous theories, the DNA analyze of these individuals indicate that the early settlers did not stay in Papua New Guinea, have kids and then traveled further east. In essence, they did not move across the pacific ocean islands hopping from one island to the next.

The ancient individuals carried no traces of ancestry from the people who settled Papua New Guinea more than 40,000 years ago. In contrast to all present-day Pacific islanders who derive at least one-quarter of their ancestry from Papuans. The genetic traces of modern Papua New Guineans would instead be explained by much later and subsequent migrations from there.

“This is the first genome-wide data on prehistoric humans from the hot tropics, and was made possible by improved methods for preparing skeletal remains,” said Dr. Ron Pinhasi at University College Dublin, a senior author of the study. “The unexpected results about Oceanian history highlight the power of ancient DNA to overthrow established models of the human past.”

The paper, “Genomic Insights into the peopling of the Southwest Pacific,” was published Oct. 3 in Nature.

Reference:

Pontus Skoglund et al. Genomic insights into the peopling of the Southwest Pacific. Nature, 4 October 2016. DOI: 10.1038 / nature19844

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55136/b1b0b614-5b72-486c-901d-ff244549d67a-350x260.webp)

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55124/79bc18fa-f616-4951-856f-cc724ad5d497-350x260.webp)

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com](https://www.illustratedcuriosity.com/files/media/55099/2638a982-b4de-4913-8a1c-1479df352bf3-350x260.webp)